The Women of the Posters: A Christianity Caught Between Tradition and Revolution

What can the posters above tell us about Chinese Christian religious devotion? What can they tell us about the ideals of a Christian woman? What can they tell us about Chinese women?

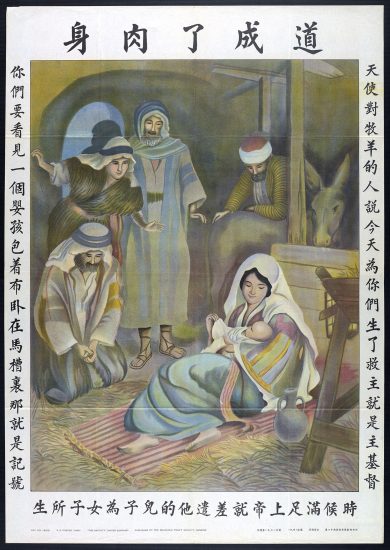

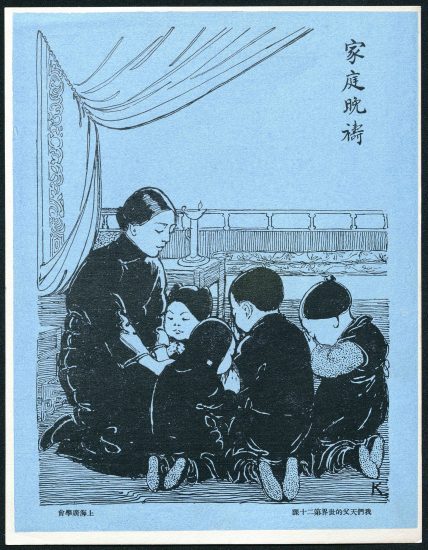

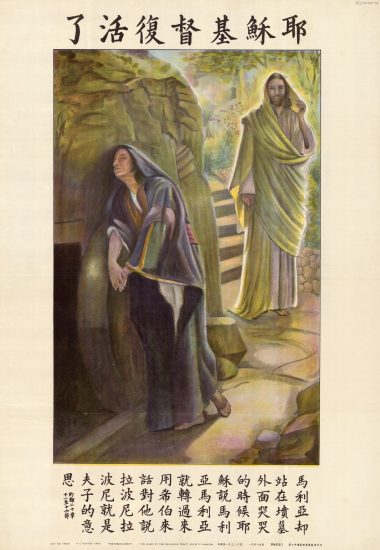

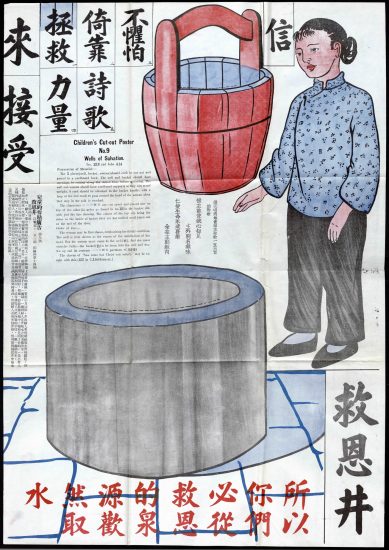

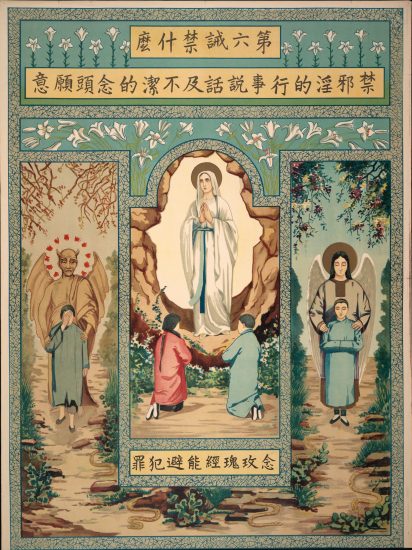

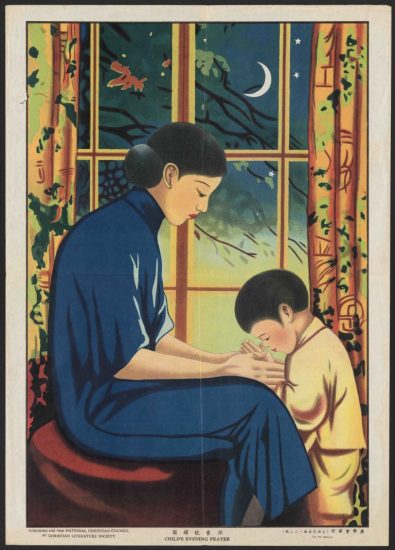

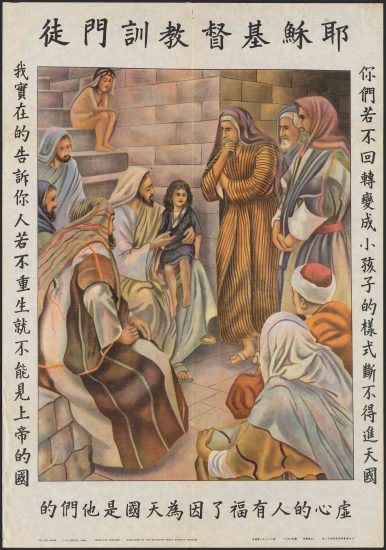

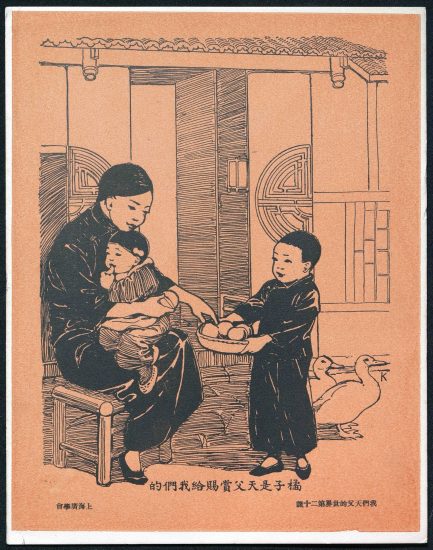

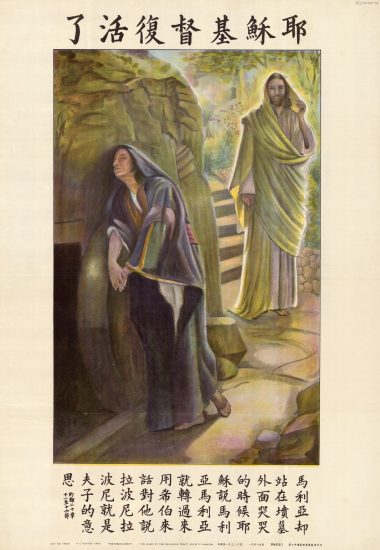

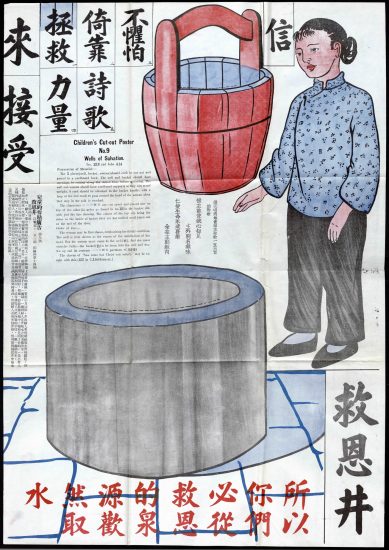

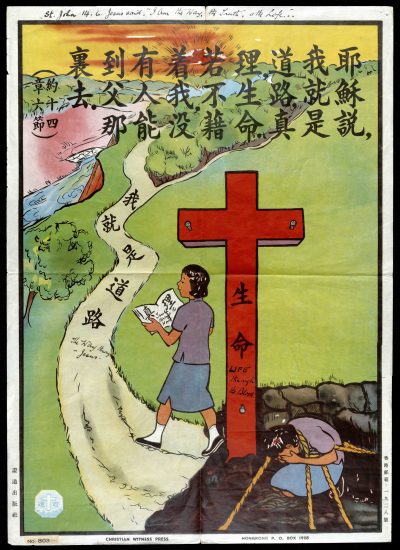

On a surface level, the above display is intended to allow us to start making connections between the posters, history, culture and Christianity tradition. My initial interaction with the images tells me that Chinese Christian practice and Chinese womanhood are closely tied together. Notice how I have paired an explicitly Christian poster of bible stories or religious devotion (The Nativity, Jesus meeting Mary at the empty Tomb, The Devotion to the Virgin Mary, Jesus holding a small child) beside a seemingly everyday Chinese poster (Chinese mother saying night-time prayers with her children, Chinese woman encountering the Living Water, Chinese mother with her praying son, Chinese mother holding her small child).Pairing the two types of posters side-by-side illuminates the way in which the Chinese Christian posters that profile motherhood and Christian spirituality can be seen as a continuation of the Biblical narrative in a localized context while simultaneously revealing how the designers and artists viewed women in Chinese society and church.

The following simplified messages can be observed from the scrolling scenes above:

Chinese Christian women are a part of the continuing story of women nurturing the life of Christ through childbearing.

Chinese Christian women encounter the life giving love and forgiveness offered by Jesus.

Chinese Christian women are examples of piety and honor to their children who they raise as faithful Christians.

Chinese Christian women follow in Christ’s teaching by embracing their role to nurture and care for children.

With the religious and cultural milieu of early to mid-twentieth century China our context, let us enter this exhibit to discover what the posters can tell us about Chinese Christian women as they relate to family, society, Christianity and culture at large. The posters in the collection were published and distributed by Christians between 1927 and 1949 and in ways they can speak to the continuities and discontinuities of the centuries old Chinese culture in the time period when Nationalist, Communist and Christians offered visions of society and the future.

Christianity’s presence in China throughout the twentieth century influenced social relationships of those who heard and received its message. The Chinese Christian Posters offer a window into some of the ways that the Gospel message interacted with Chinese culture. The posters reflect how Christian teaching depicted as images endorsed, opposed, confronted or reframed contemporary culture of the mid-nineteenth century. On either side of the Christian poster messages, or mixed in the middle, were the posters published by the Nationalist Government and the Chinese Communist Party. The Christian Posters, as we will see in the exhibit, seem to lean towards Nationalist sentiments and ideals of a “new China” that is still faithful to the past.

In this exhibit, I will peer through this form of material culture to discover some of the messages they portray about the lives, roles, purpose and cultural value of Chinese Christian woman. How did the Christian teachings brought by missionaries and adopted by local Chinese people affected the lives of Chinese women? Was the Christian message doubly oppressive, adding a new religious obligation to the already entrenched Confucian male patriarchy? Was the Christian message a means of Chinese women’s liberation from patriarchy, a doorway into public life and professional work, and an agent of redefining social and family relationships? Was the Christian message the fuel for radical revolution that included women’s rights and Chinese feminism? In all cases, the Christian posters were published during a politically polarizing era between the Nationalist and Communist parties. While the posters are Christian in message they also contain a political undertones that could be seen to align with either ideology.

Through this exhibit I will demonstrate that the Chinese Christianity displayed through the posters attempted to create a middle way for Chinese women between the tensions of tradition and radical revolution. In many ways, the posters will show how Christian teaching of family, womanhood and motherhood reinforced the centuries old Confucian values. This conciliatory Christian message would not have given husbands, fathers and sons any cause for alarm. And it would have been mostly men that saw the posters, for they were the only ones permitted to move freely in public while women were secluded to the home (Kwok 1992, 74). The pietistic women portrayed in many of the posters through this exhibit would likely have aimed to garner public respect and admiration for the goodness of Christian people, especially Christian women and mothers. These posters show women as obedient wives, diligent housekeepers, and faithful mothers. The posters in this section affirm and uphold the traditional Confucian understanding of women as subject to her father, husband and son, yet expand their traditional role towards an “educated motherhood” that could help modernize the nation (Kwok 1992, 106). On some levels the posters uphold the alliance between the successful Chinese State and Confucian-ruled family (Johnson 1985,2).

On another hand, the posters offer insight into the ways that Christianity and the Christian church was creating a middle way and middle space for women to function in society (Kwok 1992, 70). In the section “Reformed and Redefined” I highlight the posters that reveal Christianity’s vanguard message to women and society. The Chinese Christian women depicted in the posters were models of subversive gender reform through service and faithfulness that could be received by traditional Confucian standards (Kwok 1992, 109). While not an overt challenge to the traditional system, In these posters hint to trend towards missionary education for girls that produced women as teachers and nurses. To think of women functioning in the social sphere outside of their homes was revolutionary, but the Christian posters only subtly suggest this. We also will see that in the case of the evangelistic cause, women could stand alone as individuals in need of salvation and receipt of forgiveness and freedom from sin. Women can read. Women can seek God. Women can serve others outside of the home, which hints to the idea that women did not need to be married and therefore could be free from patriarchal control. These posters do not explicitly say anything close to that, but they do hint at a subtle suggestion of a middle way for women through Christianity.

To end this exhibit, I will highlight some of the later Communist Party posters and how they depict women in the family and society. Clearly, to the Communists, a restructuring of society was necessary to ensure a modern and equitable China. Their idea of restructuring included an overhaul to the Confucian value system that they blamed as China’s weakness against the strong imperial forces of the West (Rosenlee 2006, 1). A “New China” needed to revolutionize the role of the family and women in society. It is valuable to see these posters, albeit from a later date and the position of the victors of a long deleterious war. The Communist Posters offer a comparative case to the Christian and Nationalist depictions of Chinese women essential to each groups ideals of nation-building. The Communist Party of China saw it essential to liberate women from the oppression of traditional relationships and society in order that they could participate in a thriving economic system (Johnson 1985, 15). The revolutionary measures that Communist China would eventually take to erase the Confucian constraints on women and the family were directly related to restructuring society, but as many Chinese women would experience, the Communist ideal of liberated women still fell short from practice that could not free itself completely from tradition.

When viewed together the posters reveal a diversity of narratives for Chinese Christian women. Some point to a renewal of traditional Confucian roles, others hint to redefined roles for women through Christian service and faith and others push female ideal to the brink of revolution rooted in extreme socialism. It is from within this tumultuous time of political struggle, war, revolution, immense poverty and famine that the Chinese Christian Posters emerge as a witness to the ideals of the Christian segment of the population. Let us see and hear what they have to say about Christian women of twentieth century China. Do they truly represent a middle way for Chinese women of the twentieth century?

There are over fifty-five posters on https://ccposters.com that feature women as main or prominent subjects. There are many more that contain girls and women and girls in crowds or groups. The selections in this exhibit are limited to the exploration of how Chinese Christianity did or did not renew, reform and revolutionize women’s roles, identities and place in an emerging “new China”. That is to say, you are not limited the the poster selections that made it into this exhibit. Feel free to go to the website. Search and explore the myriad of material artifacts of the Chinese Christian Posters. And in your exploration, you may find posters that contradict what I have complied here. Excellent! Let’s continue the discovery process together and add your questions and critiques to the comment section at the end of the exhibit. What is presented here is by no means an exhaustive work. It is a beginning. I hope that you will engage with the images and my thoughts on them with an openness and an inquisitive mind and heart and add to the conversation and inquiry.

As a disclaimer, I am looking at these posters from my cultural and social location as a twenty-first century white, western female who is a professing Christian. I have interacted with these posters without specialized knowledge in Chinese cultural history apart from the research I have done with the intent to understand the historical, cultural and social context. My position certainly influences my assessment and the connections I have seen in the posters. And yet, this is the invitation of material culture – open to all eyes and interpretations from the time they were created into the future. I have sought to frame my analysis in charity and empathy, referring to scholarly work to help me ground my interpretations.

A word on format Each section contains the main posters I have selected to analyse. There are more posters that fit into each category, but for purposes of simplicity, I have only selected one for each sub-heading. The dropdown boxes with headings that exist as the summary points of my conclusions for each image. Be sure to view the images in each section to gain an idea of the reasons why I make the connections to history, culture and social relationships that I do. Perhaps you will not see what I saw in the images. Perhaps you will see more.

A final suggestion before you get started As you view the images and the dropdown boxes, I invite you to engage critically the following questions: Who is the subject of the poster? Who are the main and minor actors? Why could this be significant? What are the colors or positions of the objects and what might that be saying? Who or what is missing from the poster or setting? How could this be significant? What could be the intended messages of the poster, with or without the script? Who was the intended audience? What does that tell us about the artists, designers and publishers? How do the posters fit within the broader social and cultural context of twentieth century China and Christian history in China?

Tradition Renewed

The Chinese Christian Posters present women in culturally appropriate relationships, locations and behaviors. After the 1911 Revolution the centuries old Confucian system that was wrapped up in the autocratic system was discarded and China was grasping for new ways to define their state and their family structure (Kazuko 1989, 93). As the following posters reveal, the Confucian ideals, values and social structure that had governed Chinese society and family for centuries did not disappear overnight. China may have been radically changing in the years the posters were produced, but the Christian portrayal of women seemed less than radical. In fact, in many ways the Christian posters seem to have worked to uphold the traditional Confucian roles of female “servility, passivity and self-effacement” (Johnson 1985, 1). In this way, the Christian Posters appear to have leaned heavily upon traditional Confucian female subordination repackaged using the Christian scriptures and Victorian notions of the Christian family and virtuous woman who maintained comfortable and clean homes (Kwok 1992, 107). It will become apparent through this section that the Chinese Christian woman of the nineteenth century was not that far removed from the traditional Confucian Chinese woman, at least not as presented in the following posters.

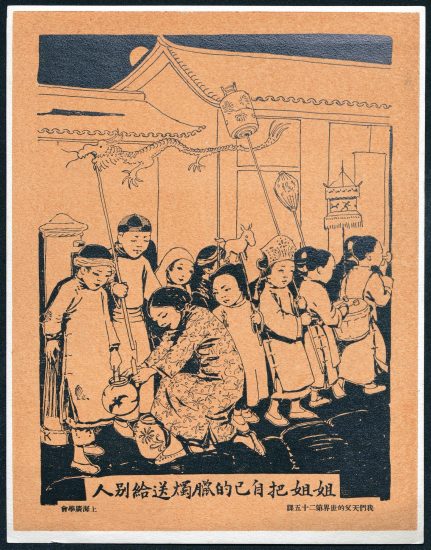

Sister Giving Her Own Candle to Others. The honorable sister offers what she has for the sake of others, but the title of the image is somewhat misleading. Sister does not just offer her lantern to anyone, but to a boy. This image reinforces the girls lower status and the boys higher status. The girl in the poster is clearly older, but in keeping with the patriarchal Confucian system the girl’s well-being is dependent on her father, brother, future husband and future son. This self-effacing sister reflects the traditional Chinese system of low status women dependent on higher status men (Johnson 1985, 8).

Obedience that Binds

What’s Your Hope, (above) a Catholic poster, offers comfort for faithful Catholics who believe in the Holy Church. This poster also indicates the familial roles of the elevated father, whose face we can see. He is the clear leader, holding the crucifix and gazing upon the Virgin and her Son. The mother, son and daughter all face the father, but the sons face can be partially seen. The mother and the daughter remain hidden, alluding to the dutiful female role that is subject to the obedience of father, husband and son. This poster reflects the clear Confucian value of the “Three Bonds of Obedience” clothed in Chinese Catholic garb (Johnson 1985, 1). This Catholic family offers teaching in the catechism while reaffirming the Confucian male dominated order and hierarchy that was thought to produce obedient and filial children and imperial subjects (Johnson 1985, 2).

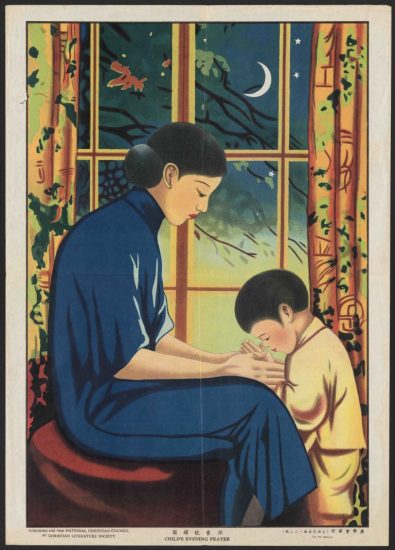

A Child’s Prayer (below) beautifully portrays a Christian mother accompanying her son in prayer. The focus on the son, both in the title, in his golden colored bedclothes, and in the spiritual discipline of prayer, reflect which person holds the authority and status. The mother’s hands hold her sons’ hands, but her face reveals that she is not praying with the earnestness of the son.The mother’s face appears passive, reserved and somewhat sad. It appears that she is simply assisting the son, who, according to Confucian tradition, is the source of her status and respect in life (Johnson 1985, 10). The Child’s Prayer, or the Son’s Prayer, reflects a Chinese Christian mother’s servitude to her son. Her duty to disciple him in the Christian way also may ensure her future well-being and respectability.

This Poster is also one of the few Christian Posters in the collection where we see a clear side profile of a woman’s face. The other posters that show a side or front profile have husbands or sons present or are depicting a woman’s work in the home. There are a few exceptions, but the subjects seem to be older women or younger girls.

In history, the Chinese family was seen as a model for the State, both defined and governed by Confucian teaching (Johnson 1985, 2). This concept of the family and national identity seems to carry over in the posters, now with Christian undertones. If it was women who gave birth to Chinese citizens, it would be Christian women would would give birth to Chinese Christian citizens. The images presented in this sub-section demonstrate the female family values of work and virtue confined to the home that carried over from the Confucian family ideals to the Christian family ideals.

Women's Place in the Family

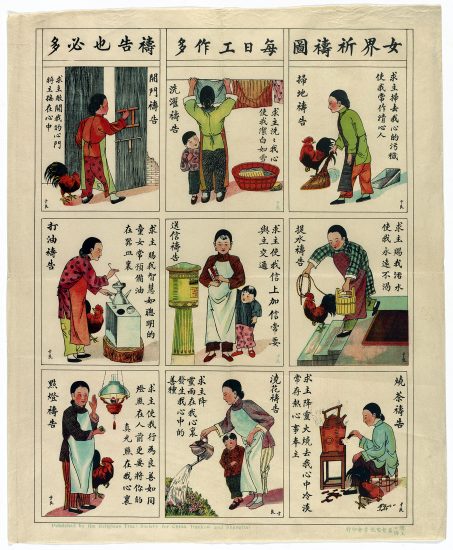

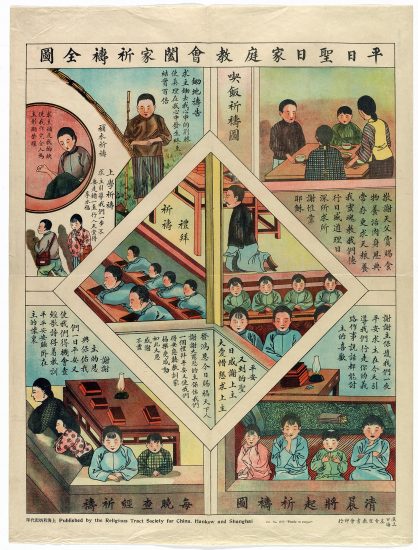

Pictures of Prayers for Women – Everyday Work Much, Pray Much (left) and Family at Prayer (above) marry the routines of domestic life with Christian prayer rhythms. Prayers for Women highlights “much work” depicted in this poster all takes place within the Confucian norms of the home. Other than the addition of the words of prayer that add a spiritual dimension to each task, this would have seemed a normal “day in the life of” for rural and lower class Chinese women (Johnson 1985, 14). It is also interesting to note that in none of the frames the woman is alone. She is either accompanied by her young son or a rooster, both male beings. Family at Prayer, while more focused on the children and broader family praying together, the woman in the family is less in focus apart from serving her family a meal and praying herself.

The substance of the woman’s prayers add a hint of her individuality and self-determination in relationship with the Lord. The woman’s work, then, is still confined to the home which was understood to build up the family and support the male hierarchy of family and state (Johnson 1985, 14). We do begin to see a glimpse of female Christian devotion that is intimate with God and rooted in devotion to Christ.

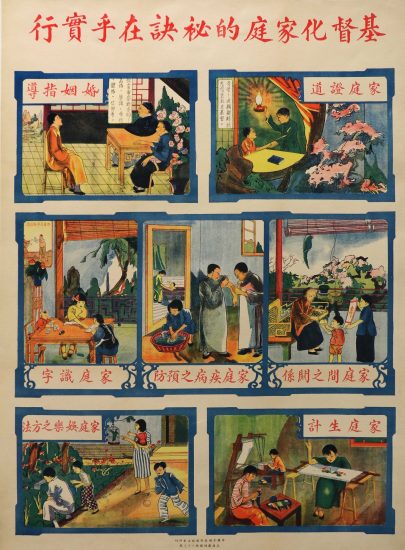

The title of the above poster makes its aim and motivation clear: The Secret of a Christian Family Lies in Behavior. The women’s behavior in the poster largely upholds Confucian norms, with the women working in the cottage industry, nurturing children, and cleaning the home (Johnson 1985, 14). The dress of the mother in the bottom left frame is western and modern, perhaps indirectly challenging the traditional norms. And yet, the women in the frame are not challenging the hierarchical order of culture and society. This poster suggests that women’s domestic duties outline their role in the Christian family. There is some incongruence in the mother teaching her children, assuming that the Chinese Christian woman is educated and literate. This “new vision” of the educated mother was an imported idea from the late nineteenth century, chiefly through missionaries Allen and Richard. The Chinese reformers Kang and Liang adopted this idea as a way to revive a nationalist view of traditional motherhood (Kwok 1992, 106).

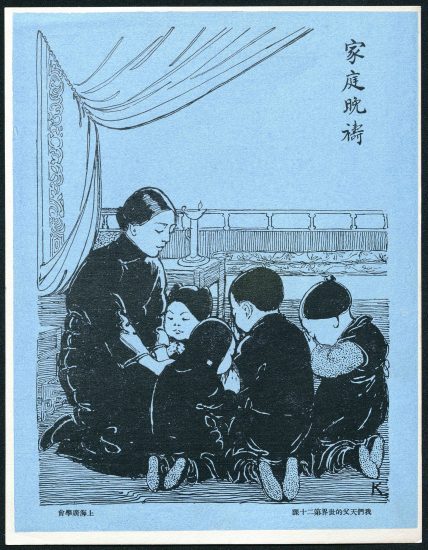

Family Evening Prayers (above) offers insight into the source of a woman’s power in traditional society that seems to be affirmed and upheld by the notions of a Christian woman and mother. The mother pictured above is dutiful in her discipleship of her children, leading them in Christian prayer before bed. For this mother, and for women of her era, her children and especially her sons were her only hope at any social significance and respect.

Within the concept of the uterine family, developed by Margery Wolf (1973, 33), Chinese women were able to secure their future comfort and success by developing close bonds with their children. The loyalty they engendered would usually factor into future control and subtle influence on the decisions of their sons and the selection of their daughter-in-laws. In the poster above the mother appears pious, chaste and close to her children, but the hidden story is one of her personal interest in keeping a close uterine family that practices the faith she holds dear, ensuring that she will be able to practice Christianity freely in her older age.

The Christian religious framework pictured in Family Evening Prayers features the mother in a prominent role and the father is absent. The sons surrounding their mother are her only hope for a good life, reflecting the traditional Confucian system that is carried forward into Chinese Christian society.

A Woman's Power

Another aspect of a woman’s power was embedded in her ability to manage the home affairs and develop cottage industry, especially in rural settings. Women were limited to the home, as demonstrated in other posters in this exhibit (Hunter 1984, 21). Acceptable women’s work included domestic chores and processing materials provided her by her husband (Johnson 1985, 14).

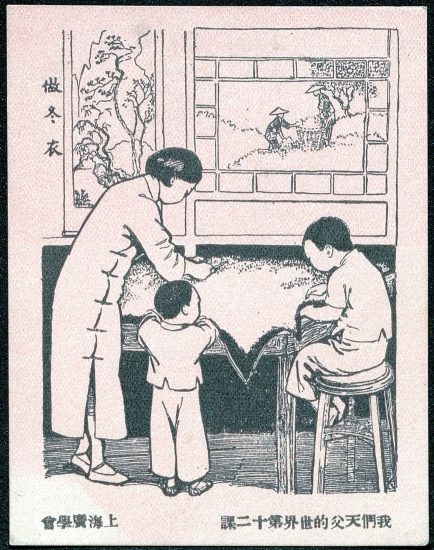

In Making Winter Clothes (above), the wife and mother is both preparing her house for cold weather and nurturing her sons in the process. One could draw parallels to the Christian “Proverbs 31 Woman” who provides for her household and is diligent in her labors. In this image, if we look outside of the house we can see a man in the distant field who I assume to be the woman’s husband working in the field. The division of male and female work true of traditional Confucian values are upheld in the name of Christianity. In fact, the Confucian virtue of womanhood was thought to be best expressed through the work of “weaving, spinning, and embroidering” (Rosenlee 2006, 81). Anytime a Chinese woman is presented participating in such work, the audience would understand that the woman is upholding the female virtues of woman’s work in the appropriate secluded context of the home.

On an economic level, the woman in the above poster is likely not a typical peasant women who would be more like to be working in the fields with their husbands and sons (Johnson 1984, 14). She appears neatly dressed and traditionally feminine, giving an air of middle class status. This suggestion could have been part of the Christian message of national modernization.

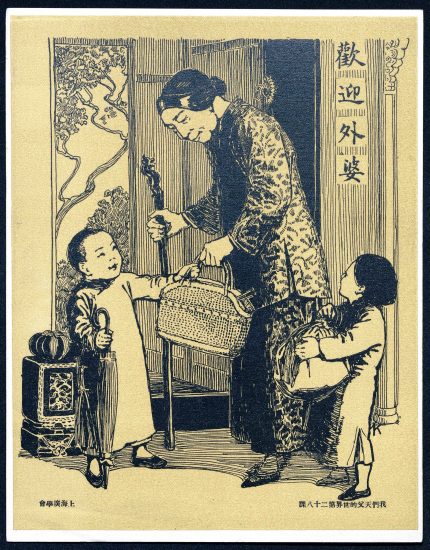

Greeting Grandmother (above) lends a light, playful attitude to the uterine family in the next generation. As Kay Ann Johnson notes, child-bearing and then marrying off male sons was a way women could increase their social status by gaining a place of authority over their daughter-in-laws (1985, 10). In this image, Grandmother is dressed well and being served. This was a rare moment for most traditional Chinese women, but the sense of honor and respect the poster alludes to seems clear. The children look happy to see their grandmother.

In the Confucian order, women learned how to gain power, even if they had to subtly manipulate their sons and control their daughter-in-laws. To the Christian intention, this poster can both promote caring for the elderly and the traditional Confucian order of women’s subordination to men that led to women learning ways to gain power through family relations.

Reformed and Redefined

At first glance, the Christian posters appear in line with traditional Confucian culture and uphold the clear gender distinctions of society (Kwok 1992, 73). A part of this may be explained by the fact that women were still secluded and not free to be in public. It was likely that the majority of people who saw the posters were men – fathers, husbands and sons. For this purpose, the Christian messages that would have been seen as disruptive to the already faltering Confucian order, may have been concealed and subtle. The presence of reformation to female identity, values and roles are present in the Posters, albeit difficult to find amid the plenty that uphold traditional roles and gender segregation. Another reason the Christian message that could redefine women’s life and work would have been concealed may have been the general belief of missionaries and Chinese Christians that faithful citizenship would come through “gradual social reform and through social services” (Kwok, 109). These next images do highlight the reformative aspects of the Gospel to the lives of women. It is important to note that the women pictured below are either young unmarried women or older women. From my survey of the Chinese Christian Posters married women are not pictured in public or apart from their children. Take note of the ways the Christian message subtly suggests a redefinition of women’s value and capability to contribute to society outside of the home.

Spiritual Equals

The foundational redefinition comes in the person of Jesus Christ. While there are no posters that depict Jesus physically present with contemporary Chinese women, there are Bible stories, like The Risen Christ that picture Jesus revealing himself to Mary Magdaline. According to Kwok Pui-Lan over half of the initial missionary literature in China focused on stories of Jesus interacting with women (Kwok 1992, 47). An overview of some missionary tracts and art work note that women were portrayed in half of the pictures (49). This fact seems underrepresented in the posters in this exhibit, but it makes sense given the majority of the posters in the CCP Collection deal with education and social life.

Mary Martin, a Western missionary wife, told the Shanghai Missionary Association that Jesus’ example of his treatment of women elevated women’s status (Kwok 1992, 50). Not only did the Western missionaries preach a Gospel message that elevated women, but the example of Western women coming to China alone and functioning as leaders, preachers and teachers was an example that spoke to the Chinese girls and women who encountered foreign missionaries (Hunter 1984, 26) but Chinese Christian women felt that Jesus’ treatment of women in the Bible was a strong support for their desire for equal rights in church and society (Kwok 1992, 51).

The message of Christ was ideologically offensive to the Chinese system of society and religion. It turned out that by telling women that they could receive salvation through Jesus Christ alone, Christianity was creating “disobedient wives and daughters refusing to worship the idols when told” (Hunter 1986, 230). Perhaps this cultural friction was mediated by posters of submissive and obedient wives and mothers and church policy that enforced gender segregation (Kwok 1992, 73). Either way, the message of the Gospel brought division into traditional Chinese families where the male members led faithful ritual to ancestors and sought to protect the patriarchy for deep rooted religious, personal and cultural reasons.

The message of Christ’s love and freedom from sin was for women also. The poster Wells of Salvation (below) declares that girls, and women, can experience the living water of Jesus. Interestingly, in a woman’s domestic work, God draws near to her and meets her with salvation and love.

Coming to the Father (right) shows a woman tied down by sins who is then set free at the cross. This woman, walking away in her Western modern dress, is reading the “book of truth”, or Bible. The image elicits feelings of independence and freedom through the cross and the ability to read the Bible. This is one of the few posters where a woman is pictured alone and the path she walks along is the “Way” assuming that a woman can follow Jesus and make her own decisions. This woman’s life is transformed by the cross and made free to be an individual. This goes against Chinese traditional culture, but offers perspective to the way the Gospel attempted to reform and redefine women’s value, identity and place in Chinese society.

Women as Ministers of the Gospel

The posters that highlight messages and images of evangelism feature women in varying social contexts. These posters include women as subjects of Gospel preaching and allude to women participating in Gospel work if only through the fact that if women can receive forgiveness they can also share that message with the women in their lives. There are no posters that depict Chinese women in active evangelism, such as the Bible Women who continued the Chinese Christian heritage that began with Candida Xu and continued through the waves of missionary impulse during the period of the posters (Lutz 2010, 224). While they do not emerge in the posters, scholars know that they were working behind the scenes.

The major strategy that Chinese women heard and saw the Christian message was through female mission schools (Hunter 1984, 234). While the majority of Chinese people did not look favorably on female education or the missionary schools, there was some influence, especially after the 1911 Revolution and China’s attempt to modernize. By and large, the majority of women who became Christian through mission efforts in the early twentieth century were lower class peasants from rural areas mostly because women missionaries had more opportunity to interact where Confucian structures were more lax (Hunter 1984, 234)

Christian conversion and ministry may have also provided Chinese women a new identity and independence from the strict Chinese family systems they were accustomed to (Hunter 1984, 241). While some women chose to follow Christ because of the promise of escape from the family hierarchy, others found meaning in the Christian work of teaching, preaching and nursing.

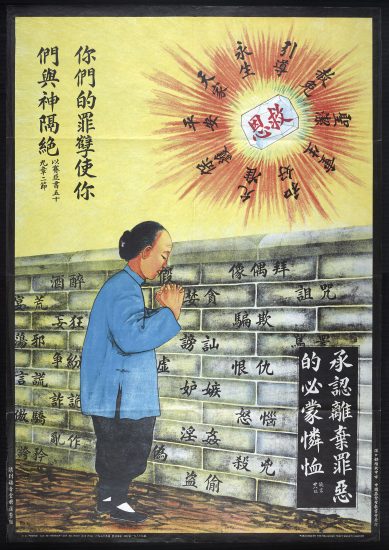

Sin As ‘Barrier’ (above) simply demonstrates that women could be reconciled to God through the confession of their sin. If women were separated from God because of their sin and not because of their gender or lower status, then they could be made right before God as women. The fact that women’s gender and femaleness did not exclude them from salvation would have spoke deeply to the marginalized, disenfranchised women. It is also important to note that the woman pictured in the poster is an older woman who already has certain respect in society that honors elders.

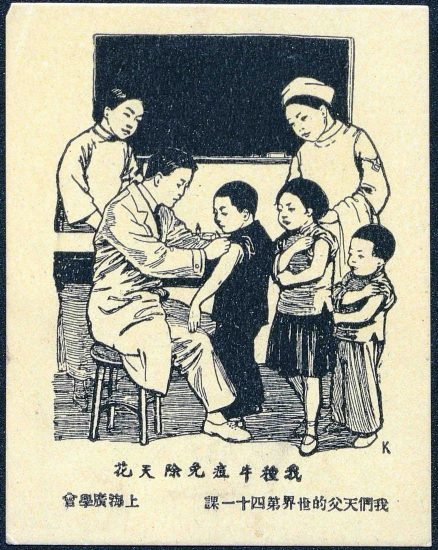

I Get Vaccinated To Guard Against Smallpox (above) displays a Chinese woman as a nurse. This redefined social work for women was a product of missions schools. Young Chinese women who attended mission schools had the option to become teachers or nurses, and some doctors (Kwok 1992, 116). Many of these Chinese female professionals worked in mission schools and hospitals alongside their former teachers and Western missionaries.

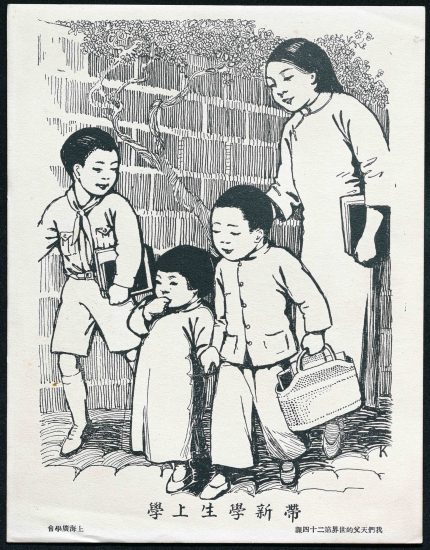

Guiding New Students to School pictures a young Chinese woman as a teacher who accompanies Chinese children to school. The woman holds her books under her arms. It was the example of Western missionaries for many young Chinese women in mission schools who developed a desire to follow in their mentors footsteps (Hunter 1984, 249).

Revolution

The Chinese Christian Posters presented gentle reforms to Chinese culture that generally aligned with Nationalist sentiments.* The social transformation that people were longing for during the decades of instability and war was ultimately not met by the “gradual reform and social services” that Chinese Christians and missionaries supported (Kwok 1992, 109). What would come was a militant, radical revolution under the Communist regime led by Mao Zedong. The Communist Revolution and reconstruction that proceeded was committed to the a radical overhaul of Chinese society. The platform of modernization included the liberation of Chinese women, particularly for participation in the economic modernization of the country (Johnson 1985, 15). While the Communist posters featured in this section are from a later time period, the subjects presented are for the point of comparison with the older Christian and Nationalist posters that uphold a neo-Confucian interpretation of Chinese women’s traditional roles. The Communist posters below do not completely throw off all Chinese tradition, but they do present women in central roles outside of the home which is a significant departure from the Christian Posters that largely upheld women’s domestic obedience. Keeping in mind that the Communist Posters were used for propaganda and the reality of the change to women’s lives were seen as secondary issues in the establishment of Communist China, the social presence of women and their exertion of public leadership and agency in the posters is impressive (Johnson 1985, 84).

*The alliance between the Christian Posters and the Nationalist New Life Movement can be seen in some posters showing the “Blue Shirts” wearing small pins in the shape of the cross and the various other Nationalist posters in the Chinese Christian Posters Collection (Schoppa 2016, 208). The New Life Movement was neo-Confucian and fascist in orientation and ultimately lost any influence or power after the Communist victory.

Chairman Mao Gives Us A Happy Life (above) was produced in 1954 and is displayed at chineseposters.net. It pictures the modern, prosperous Communist family. Their home is clean, full of western style furniture and their clothes are also western. The woman remains in the role of wife/mother/caretaker, which does not change in Communist poster. her clothing and full pictured smiling face are different. The modern Chinese Communist mother benefits from the economic prosperity that she enjoys through her husbands work and the freedom given her through the nuclear family structure. She still cares for and nurtures her children, keeping a clean and tidy home and knitting (blue garment at the bottom right of the poster). While this poster reflects the benefits of modernization and the bliss of mutual love in marriage and family that was freed from the Confucian social order, it still maintains a woman’s place as caregiver and mother.

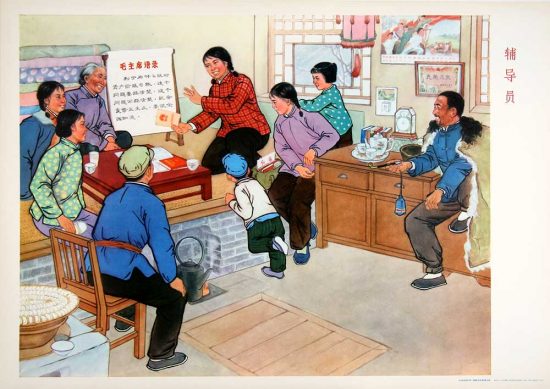

The Counsellor (below) offers an excellent counter narrative to the Christian posters that show women as “educated mothers” and teachers. In the Communist poster, woman is teacher, political leader and public influencer. This idea would have been revolutionary to the traditional view of women. Not only is the new Communist woman free to interact with the public, she is also able to influence and contribute to the social system outside of the home. Notice how the men are laughing and captive to her teaching and the women are smiling and at ease.

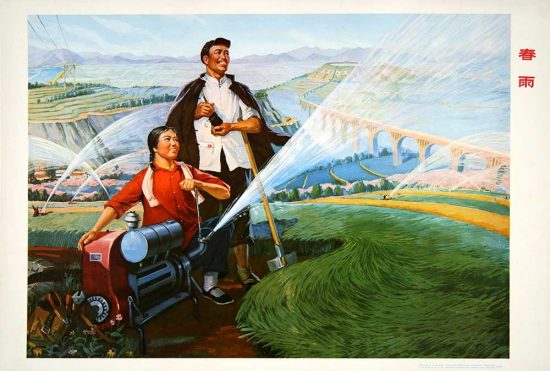

Spring Rain (above) shows a peasant woman operating new technology that has produced a bumper crop. The woman, who is wearing the prominent Chinese red, is in the position of power. She is the future of agricultural production, while the man is holding the shovel -the symbol of physical labor and traditional agricultural practice. The woman is in the fields with a man, something that would have been acceptable in the old China, but in the Communist project, she clearly could be doing this work on her own.

Poster retrieved from: https://www.abebooks.com/art/chinese-propaganda-posters/

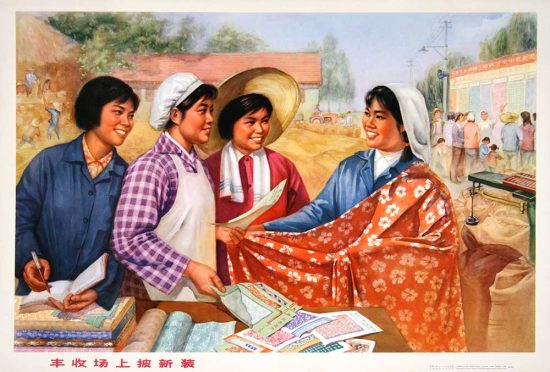

In New Clothes, Bumper Market (below) four Chinese women are working in the public sphere independently of men or family restrictions. They appear happy, intelligent and prosperous. While the women are still engaged in the business of clothing which touches on domestic life, they are seen as skilled workers in their buying, selling, reading and writing. They reflect the ideally economic productive, happy new Chinese women of the Communist regime. What we do not see is the demands that are still expected of them in their home life, but that was not the point of the poster.

A Middle Way : Lost, forgotten or hidden?

This exhibit has profiled some ways in which the Chinese Christian Posters offer insight into women’s lives during the early to middle of the nineteenth century. The Christian Posters reveal how the age old ideals of the obedient, domestic, secluded woman, wife and mother remained present in the Christian teaching and identity formation of the family and femaleness. Chinese Christian women were expected to not challenge the patriarchy and filial system that dictated their proper place in society. The posters also offer subtle suggestions towards the reformative ways that a God who was near and for women introduced into Chinese society. New roles and conceptions of a woman’s value began to emerge through the missionary education of girls and the presence of independent female missionaries. Christian teaching began to awaken Chinese women who heard the message and responded to their value and purpose beyond the family system, yet it was the Communist ideology that was willing to take revolution into all areas of society, including the family and the roles of women. The Chinese Christian Posters support the idea that Christianity and the Church offered a middle way and a middle space for Chinese women (Kwok 1992, 70) While Chinese women found their place in the middle ground of Christianity and would develop their lives as Christian women, mothers, teachers, nurses, evangelists and Bible women, many others would lose, forget or hide their faith when the middle ground was caught in the crossfires of the Communist revolution that explicitly eradicated the traditional Confucian hierarchy and gender inequality.

The Chinese Christian Posters do stand as a historical witness to the values, ideals and hopes that Chinese Christians had for their families, faith and nation in a time of great uncertainty. They speak of the lives and experiences of Chinese Christian women who were renewed in tradition, reformed and redefined by the Gospel and revolutionized by the Communist victory and its version of feminism. The ingenuity of these women who navigated their value, identity and roles as wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, followers of Jesus and ministers of the Gospel is not depicted through one single image, but together we can begin to see their strength, endurance and faith that has remained long after poster campaigns.

Sources

Fan, C. C. (1994). Chinese Women and Christianity, 1860-1927 (review). China Review International, 1(1), 160–163.

Hunter, J. (1984). The gospel of gentility: American women missionaries in turn-of-the-century China. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Johnson, K. A. (1985). Women, the family, and peasant revolution in China (Pbk. ed..). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kwok, P. (1992). Chinese women and Christianity, 1860-1927. Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press.

Liu, W. (2013). Redefining the Moral and Legal Roles of the State in Everyday Life: The New Life Movement in China in the Mid-1930s. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 2(2), 335–365.

Lutz, J. G. (2010). Pioneer Chinese Christian Women: Gender, Christianity, and Social Mobility.

Ono, K. (1989). Chinese women in a century of revolution, 1850-1950. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Rosenlee, L.-H. L. (2006). Confucianism and women: a philosophical interpretation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Schoppa, R. K. (2016). Revolution and Its Past : Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History.

Shiny, Happy People: The Art of Chinese Propaganda Posters. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2019, from https://www.abebooks.com/art/chinese-propaganda-posters/

Wolf, M. (n.d.). Women and the family in rural Taiwan. Stanford University Press.

Women as Caregivers. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2019, from https://chineseposters.net/themes/women-caregivers.php