messaging in 20th Century China

The early 20th century (prior to 1949) marked a period of remarkable boom for evangelism and the Protestant quest to win Christian converts in China; one that has continued in the country today in some form. As church historian Lian Xi notes in Redeemed by Fire, there are probably more than 50 million Protestants in China today, a figure well over 600 times what the it was in 1900. For a country and region with a storied history of religious persecutions, the era signaled a significant departure.

The rise of charismatic revivalists like Wang Mingdao and John Sung provided the needed indigenous resilience and vitality to drive the emerging movement. As Li opines, the emergence of these indigenous evangelists was characterized by a rich mix of charismatic ecstasies, evangelistic fervor, and fiery eschatology. Their evangelistic campaigns had mass appeal and their style and messaging were largely unconventional and, I would argue, effectual.

As Grant Wacker writes in his article China’s Homegrown Protestants, “they heralded a message that called not for the reform of oppressive institutions but for deliverance from them.” The result – a surge in Protestant Christianity in China. People of all ages, gender and status responded to Sung’s call to evangelize the Chinese mainland and islands. This era in Chinese Christianity was characterized by “conversion, biblical literalism, missions to unconverted Chinese, attempts to evangelize other Christian sects and fierce denunciation of mainline Christianity and liberal theology,” Wacker insists.

To get a sense of the influence of the revival movement of the time in China, a western reader might think of the wave of post-World War 2 evangelistic movements in America pioneered by the likes of Billy Graham. The work of Graham and a band of other evangelists of the time in America not only transformed the religious landscape in the country but arguably helped shaped the worldview of many, from ordinary Americans to political leaders.

As Sung and other revivalists barnstormed across China, they challenged their listeners to become involved in the business of soul winning, disciplining new converts to, as Daryl Ireland notes, “tell others about Jesus, whether speaking to them on the streets, in homes or in prisons.” These Chinese revivalists combined exegesis in the theology of the hereafter with moral teaching attuned to the deep anxieties and dreams of the day. Converts volunteered in their hundreds, unabashedly sharing their new found faith with neighbors and people they meet on the streets.

According to Tiedemann, the perambulations of these native evangelists “helped spread the Christian message through preaching in market places and roadside inns, as well as through the distribution of religious tracts.” Religion flourished in the early 1900s in China for several reasons, part of which is the ever-expanding spiritual marketplace. Converts at Sung and Mingdao revival meetings were mainly “men and women who had suffered a fracture in their lives.” Many were victims of social marginalization who were constantly in a struggle for meaning-making.

These revivalists framed what was happening in China then as a moral conflict and exhorted people to new life in Christ through their different evangelical tools. This study will examine evangelical messaging in early 20th century China with specific focus on the use of tracts as evangelical tools. I would seek to answer questions such as: how did Chinese Christian posters present the gospel of salvation before 1949, and why was the cross so prominent in these posters.

Savior, no sage

The revivalists of this time in Chinese Christian history, as Wacker explains, “heralded a message that called not for the reform of oppressive institutions but for deliverance from them.” The underlining message was that there is no way human systems can save a depraved soul. Sung openly proclaimed this apocalyptic gospel with a fiery messianic fervency and flavor in his preaching declaring at one time, as Wacker recalls, that “China needs a Savior, not a sage.”

The revivalists of this time in Chinese Christian history, as Wacker explains, “heralded a message that called not for the reform of oppressive institutions but for deliverance from them.” The underlining message was that there is no way human systems can save a depraved soul. Sung openly proclaimed this apocalyptic gospel with a fiery messianic fervency and flavor in his preaching declaring at one time, as Wacker recalls, that “China needs a Savior, not a sage.”

Though driven by corrupt and oppressive governments such as that of nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, I think that the weak side of this kind of message is that it rips its audience of any incentives to fight for issues of social justice, equality and good governance. It could make people less concerned about social justice and make them believe that only through devotion to matters of faith and religion can all of their problems be solved. It is not always the case, but odds are higher that people who attribute every human reality to God tend to have little motivation to challenge systemic injustice where they exist.

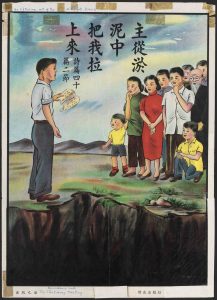

Consider the poster above, a young man stands by a pit and testifies to his salvation from the pit via the grace of the unseen God. The poster quotes Psalm 40:2 “He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire.” Attentively listening are individuals of different ages, gender and experience. This messaging bodes well with what Tiedemann sees as the emotional gospel that was fairly commonplace with assurance and testimony meetings of the revivalist movements.

Daniel Bays who sees such emotional release as a key factor helping to drive mass repentance, argue that they were strategies used to make converts see new realities “all in the context of stress on the power of the Holy Spirit to cleanse and renew the converted and to save the unbelievers.” I think of the popular “Jesus is the answer” refrain of revivalist movements in Africa. It brought a lot of people to the church, but it also turned pastors to medical doctors for all kinds of health issues for which people could ordinarily go and get practical answers in established medical institutions.

Invisible Christ, Visible Cross

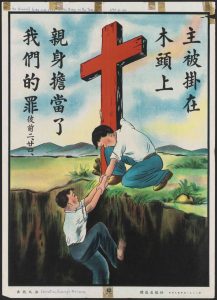

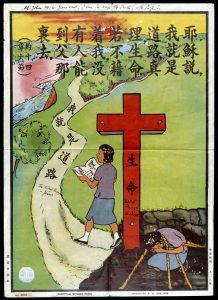

Nothing is more prominent in Chinese depiction of the salvation message than the Cross. Bold and without an image of a crucified Christ, these Cross stand tall in Chinese Christian posters of the pre-1949 evangelical era as the most significant representation of the Christian message of redemption. A remarkable feature of the 20th century revival in China was its ability to synthesize theology with culture. This is not unique to the era as it dates back to earliest years of Christianity in Asia but the revivalists elevated it in some ways.

Nothing is more prominent in Chinese depiction of the salvation message than the Cross. Bold and without an image of a crucified Christ, these Cross stand tall in Chinese Christian posters of the pre-1949 evangelical era as the most significant representation of the Christian message of redemption. A remarkable feature of the 20th century revival in China was its ability to synthesize theology with culture. This is not unique to the era as it dates back to earliest years of Christianity in Asia but the revivalists elevated it in some ways.

Scholars say crucifixion as captured in the biblical story of Jesus death is not a cultural practice in China. Historians tie the popularity of that cruel act of punishment to the Roman Empire which ruled at the time of Jesus. Having such cruelty represent the face of a religion that purports to be built on love, grace and mercy was deemed repugnant to the cultural sensibilities of the Chinese by these evangelists. Thus, the Cross with a crucified Christ was part of Christianity approach to adapt to cultural realities.

Escape

In the posters above, the salvation message was presented to Chinese readers primarily as an escape route; escape from a life of misery, uncertainty, struggle, double-mindedness, personal failures and the many failings of the socio-economic systems they lived in. The design and crafting of the message is done in such a way that readers were challenged to see answer to their intense personal longings in a new life Christ. Prevailing social and economic systems were depicted as leading to more misery, pain and discomfort while a new life as a Christian meant transformation in spiritual and earthly realities.

The charge to the readers, as Ireland suggests, was always to “return home”. Home here was not only a heavenly one, but a place where the failures of the prevailing systems will cease and new realities become real and present; where anxiety is replaced by hope and confidence; where fear gives way to new sense of security and certainty. For many of the Chinese unsettled and disoriented by immigration at the time, the escape suggested by these posters offered the type of meaning and hope that their dislocation and struggles have ripped them off.

The people for whom these messages were primarily crafted and who would later become the converts, “were peddlers, fortune tellers, night-soil collectors, bankrupt shopkeepers, underpaid missionary helpers and, of course, talented but disempowered women. Many were victims of bandits or famines or floods. Any many others were addicted to opium, desperately seeking relief from a life-crushing industry that largely owed its prosperity to western economic rapacity,” writes Wacker.

This kind of messaging inaugurated an era of radical Pentecostal beliefs and practices ad contributed to the growth of the Chinese independent churches. “Millenarianism constituted the most conspicuous feature of this radical Protestant theology. Though the details varied from sect to sect, all of them foresaw the imminent end of history in which the Lord would return in glory smite his enemies and establish a millennial kingdom of peace, justice and prosperity,” Wacker notes.

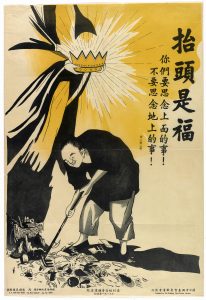

Excellence In this poster, a man labors through trash while a crown is shown above his head depicting the glory that await him if you accepts the gospel and become a Christian. In the Chinese writings on the poster, it is noted “Blessings are awaiting you from above.” That message supported with a biblical message on the poster that reads thus: “Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth.” (Colossians 3:2)How people receive a given message might differ, but generally the inferred meaning of this poster is – there is an escape from your struggles, and becoming a Christian is that escape.

In this poster, a man labors through trash while a crown is shown above his head depicting the glory that await him if you accepts the gospel and become a Christian. In the Chinese writings on the poster, it is noted “Blessings are awaiting you from above.” That message supported with a biblical message on the poster that reads thus: “Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth.” (Colossians 3:2)How people receive a given message might differ, but generally the inferred meaning of this poster is – there is an escape from your struggles, and becoming a Christian is that escape.

A feature of most Christian posters of this era in China is that described by Wacker as “bible literalism”. There is a deliberate use of biblical text to interpret or exegete on all human conditions depicted in the posters. Most of them came as open rebuke of the city culture and lifestyle emanating from the modernization of China and the mass migration triggered by it. Here salvation is presented as a lift from a life of endless toil to one of excellence and glory.

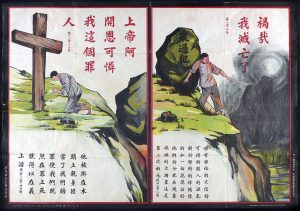

Rescue  Here a man is being hauled into a fiery pit but forces represented as a heavy stone. These forces could be interpreted to mean the lures of the fleshly or selfish desires and societal pressures; the human ambition to ‘make it’ at all costs, which often pushes people to all sorts of corrupt, depraved actions. Sin is given as the reason people suffer, and on the big rock is written “all have sinned”.

Here a man is being hauled into a fiery pit but forces represented as a heavy stone. These forces could be interpreted to mean the lures of the fleshly or selfish desires and societal pressures; the human ambition to ‘make it’ at all costs, which often pushes people to all sorts of corrupt, depraved actions. Sin is given as the reason people suffer, and on the big rock is written “all have sinned”.

On the other half of the poster, he is introduced to what life could be when lived in dependence on the Christian God – weight is lifted off your back and you have peace and strength to continue in your life-journey. This is both aspirational and remarkably enticing. It echoes to me the biblical call in Matthew 11:28 – “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens and I will give you rest.” The man on his knees in prayer has responded and is shown to be at peace living a life of dependence on God. His experience is salvation is captured by the message “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, so that we might die to sins and live for righteousness.” (1 Peter 2:24)

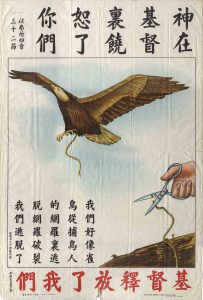

Freedom The same theme of escape is beautifully depicted in the picture of an eagle set free by a hand with scissors that cuts off the rope holding it from flying. Two bible verses are paraphrased thus: “In Christ God forgave you” (Ephesians 4:32), and “Christ has set us free” (Galatians 5:1). This poster presents Christ as the hand that liberates.

The same theme of escape is beautifully depicted in the picture of an eagle set free by a hand with scissors that cuts off the rope holding it from flying. Two bible verses are paraphrased thus: “In Christ God forgave you” (Ephesians 4:32), and “Christ has set us free” (Galatians 5:1). This poster presents Christ as the hand that liberates.

Redemption here is portrayed as something instantaneous and utterly life-transforming. The depiction in this poster is captivating, and intentionally so. Who doesn’t want to fly like eagle? Eagle is symbolic of triumph over hard and difficult challenges. Using imagery that every ordinary person can identify with was one way these posters try to reach their targets.

References:

- Chiang, Kal-shek: Essentials of the New Life Movement (Speech, 1934)

- Bays, Daniel: The Growth of Independent Christianity in China 1900-1937

- Ireland, Daryl: Becoming Modern Women: Creating a New Female Identity through John Sung’s Evangelistic Teams

- Wacker, Grant: China’s Homegrown Protestants (Christian Century, Janury 2013)

- Young, Ernest: The Politics of Evangelism at the end of Qing: Nanchang 1906

- Tiedemann, R.G: Protestants Revivals in China with Particular Reference to Shandong Province.

As Li suggests, it was the indigenous revivalists that were largely responsible for turning Christianity from an alien faith to a spirited local religion in China. Their skillful use of simple mass media tools like tracts is very instructive of how to reach a people with imagery and linguistic patterns that best captures their spiritual and cultural realities and help them get a grip of the message as intended.

The educational, spiritual, social and peacemaking mission of the church makes it imperative that clergy understands the impact of instruments like the tract. In today’s world that understanding is necessary for the work of ministry. Media platforms print, online and broadcast, are instruments made available to the church. Martin Luther’s 95 thesis is arguably the first work of the church to go viral. To continue to make the good news go viral, which is my modernist take on the Great Commission, we must strive to understand ways to communicate via the multiple mass media options at our disposal.

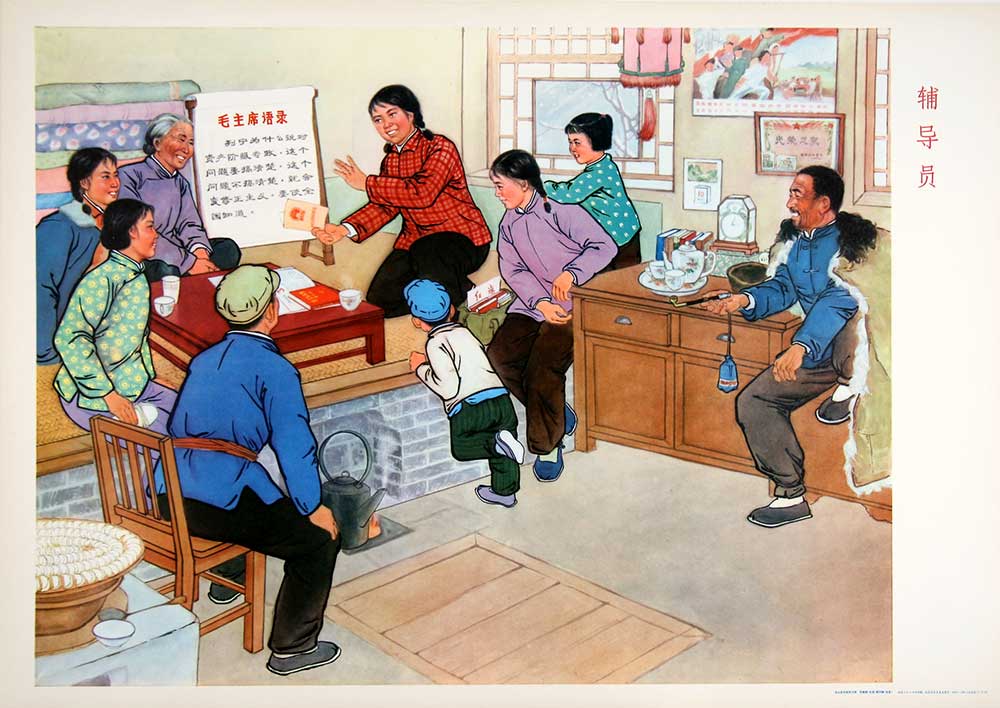

What we noticed in China post 1949 was the Communist government’s hostile takeover of art forms that significantly helped the spread of the gospel, and the turning of same into an instrument of propaganda used to suppress and subjugate the very system that considerably popularized it in years prior.