Jesus in Chinese Christian Posters as a Tool of Localizing Christianity

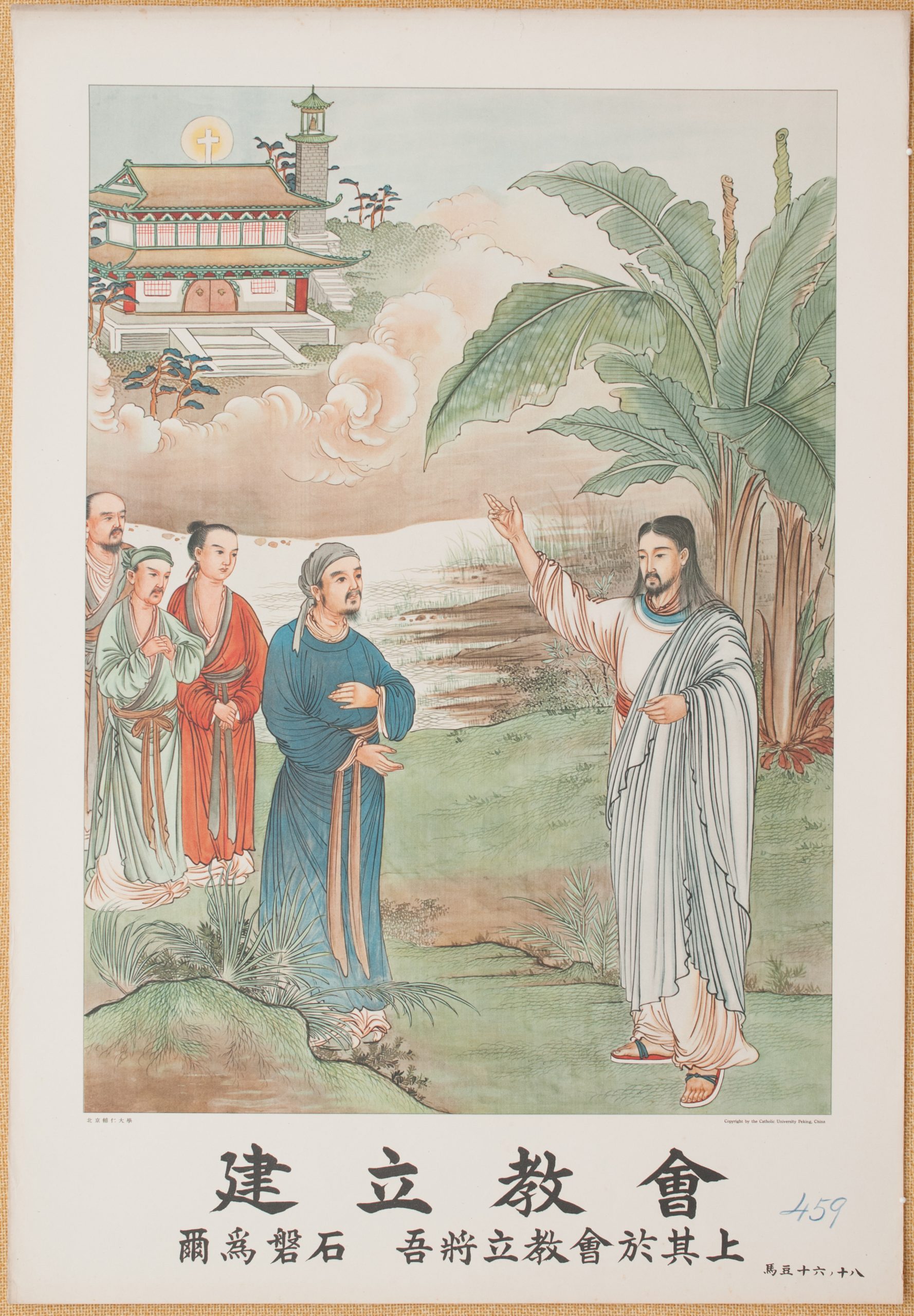

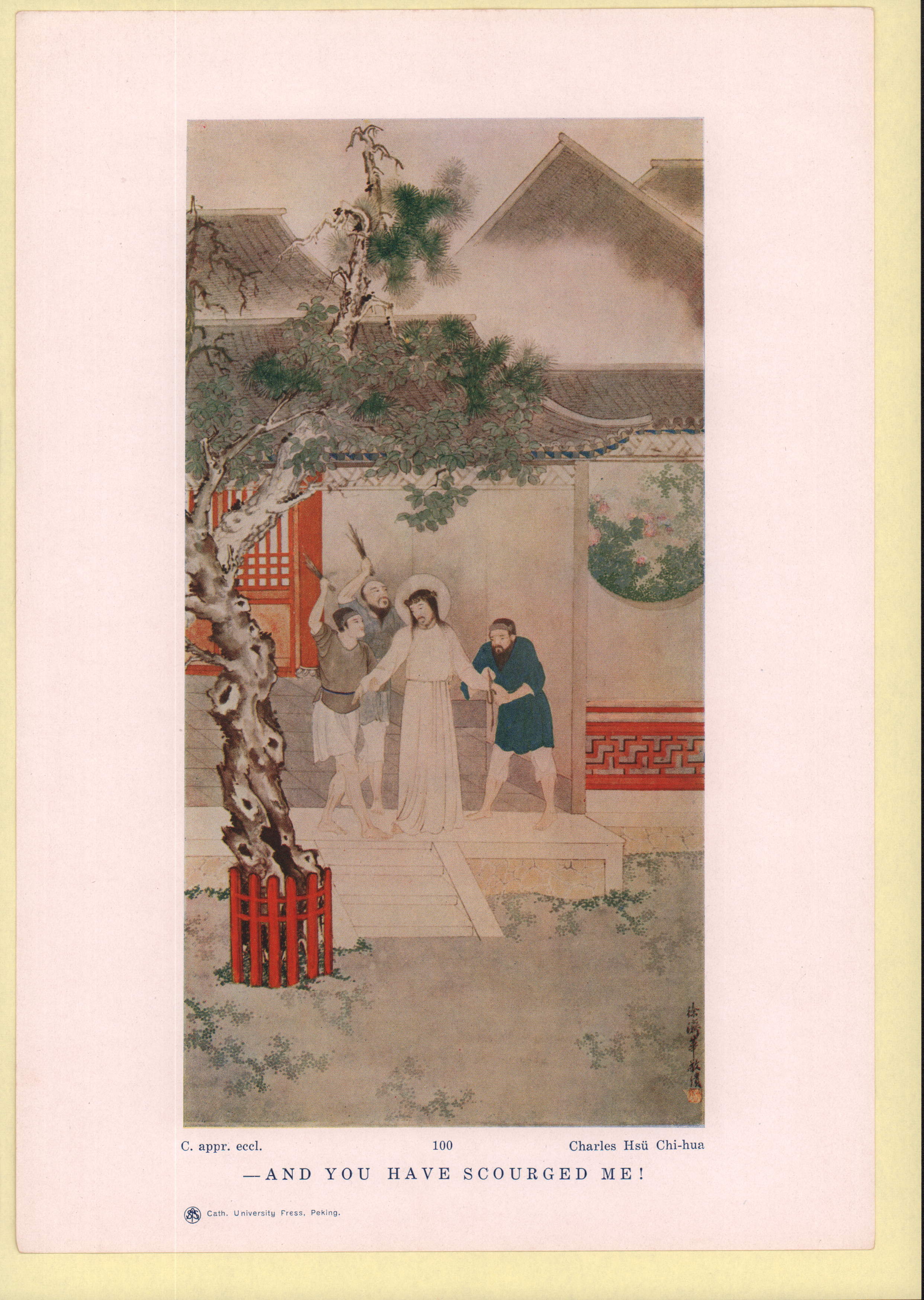

Christians in China had a vested interest in portraying Christianity as being both a local religion and as something that could mesh entirely with existing Chinese cultural norms. This was both due to the potentials of persecution and minoritization, but also due to the want to evangelize and spread the Christian faith. Portraying a prominent and emblematic figure within Christianity such as Jesus in more culturally Christian settings would not only help others outside the Christian faith view Christianity as a more local religion, but also to draw more empathy during times when ‘Western influences’ were being targeted and mitigated within China as a whole.

Christianity was by no means a recent import in the 1940s, but did not enjoy the same localization within public perception as Buddhism had in certain contexts. In order to maintain and grow, Christian missionary groups and organizations would use posters as a way to connect further with Chinese cultural traditions and art forms. This would be shown in posters from that rough time period and the emulation of not only Chinese architecture and Daoist or other religious figures, but in employing the use of Chinese symbols- such as the use of clouds in “Mary holds infant Jesus”, which were often used in symbolism of Buddhist figures to represent distance from worldly objects.

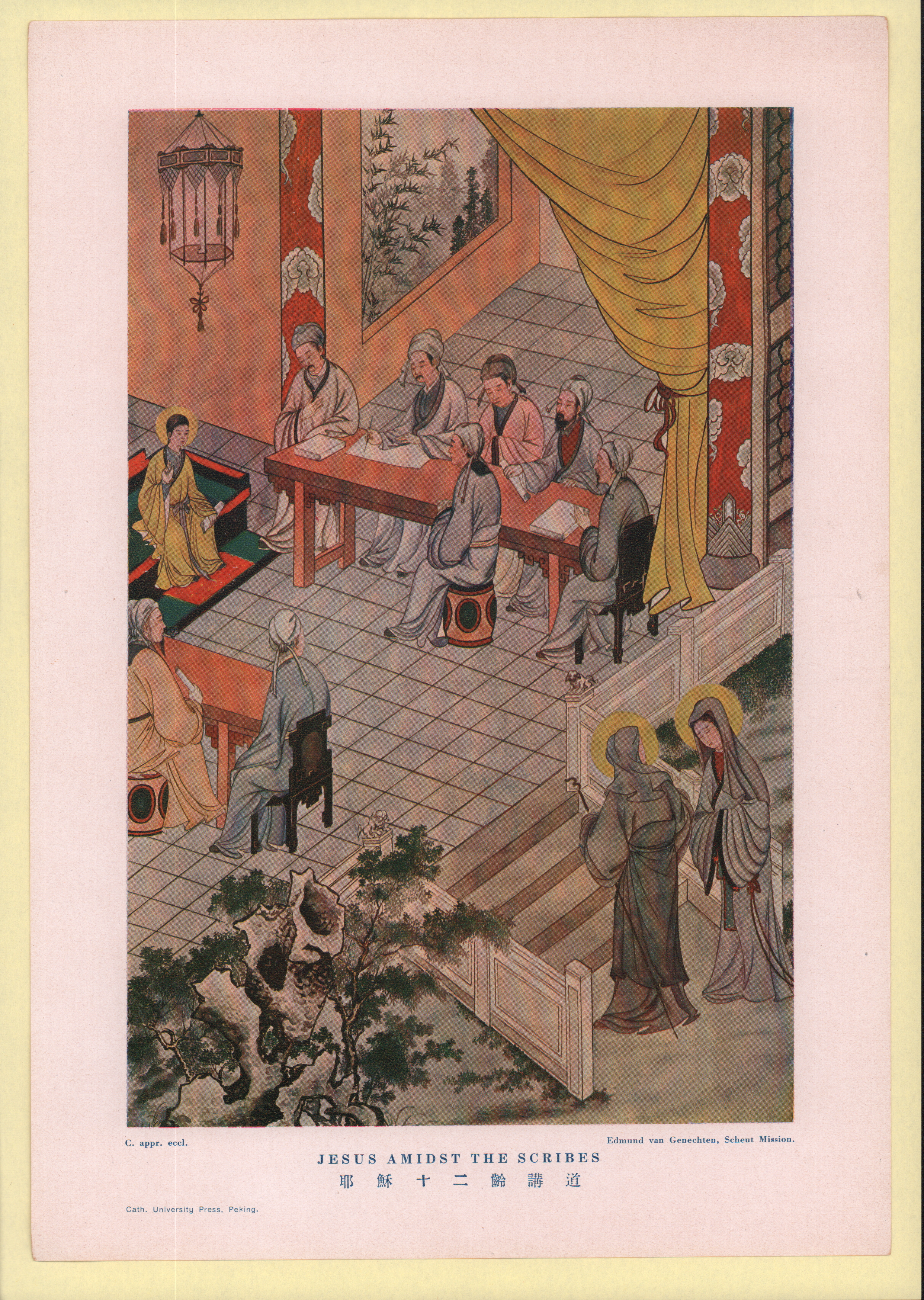

The artstyle and integration of calligraphy within some of these paintings are also similar to those of Shan shui and Huaniaohua art traditions, which further ties the posters together with the existing art tradition. One aspect also of note in terms of similarity to Shan shui art is the way in which focus is portrayed within these paintings- in the one where Jesus is sitting within a building, “Jesus Amidst the Scribes”, he is not centered via the rule of thirds, but through the direction that every other figure within the painting is looking. In regards to integrating tenets from the Huaniaohua art tradition would be that of the great detail put towards both plants and animals within these paintings, and the use of symbolic plants seen in other Chinese paintings (which would often be intentionally chosen to evoke certain values or to communicate certain emotions through a cultural context).

Stephanie M. Wong also writes in her Visions of Salvation chapter on the use of other typical art forms and the rules thereof to further integrate and reintegrate Christianity into Chinese art tradition. Her focus circles in on the yuefenpai genre, and the similarities between her selection of posters and that of this popularized print style, particularly in her quote “these catechetical images evoke the yuefenpai that were popularized in Shanghai” (Wong, pg. 192). This adaptation extends into the dress and instruments or tools that the figures are wearing and using within the selected posters, as well as their physical appearance.

The use of Chinese culture to make Christian images better adapted to local culture was also not only an intentional thing- it would be remiss not to recognize the number of local Chinese Christians whose art was influenced by their own surroundings, and the stories that they had grown up with of Christianity were therefore viewed through the lens of their local area. Jesus has been a figure often adapted to have features similar to the artist, or whose appearance is intentionally chosen to portray a certain message rather than based on the geographic location and what he may have historically looked like.

Works cited

Wong, Stephanie M. “Roman Catholicism: Painting, Printing, and Selling Morality in Modern China” from Visions of Salvation: Chinese Christian Posters in an Age of Revolution. Ed. Daryl R. Ireland. Waco: Baylor University Press. 2023.

Yee, Chiang. Chinese Calligraphy: An Introduction to Its Aesthetic and Technique. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Press. 1973.

Crane, Louise. China in sign and Symbol. Shanghai: Kelly &Walsh, LTD. 1926.