Intro

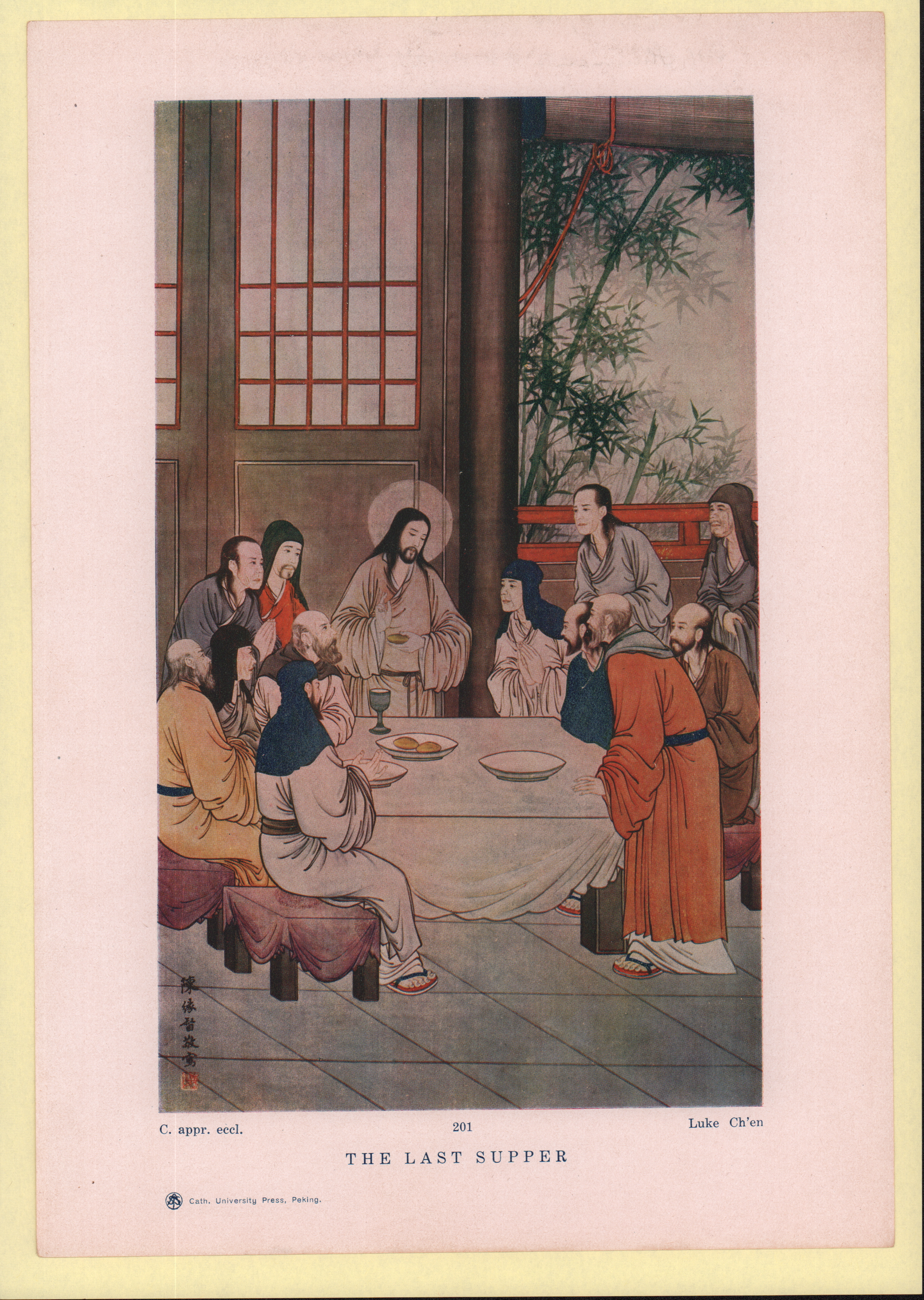

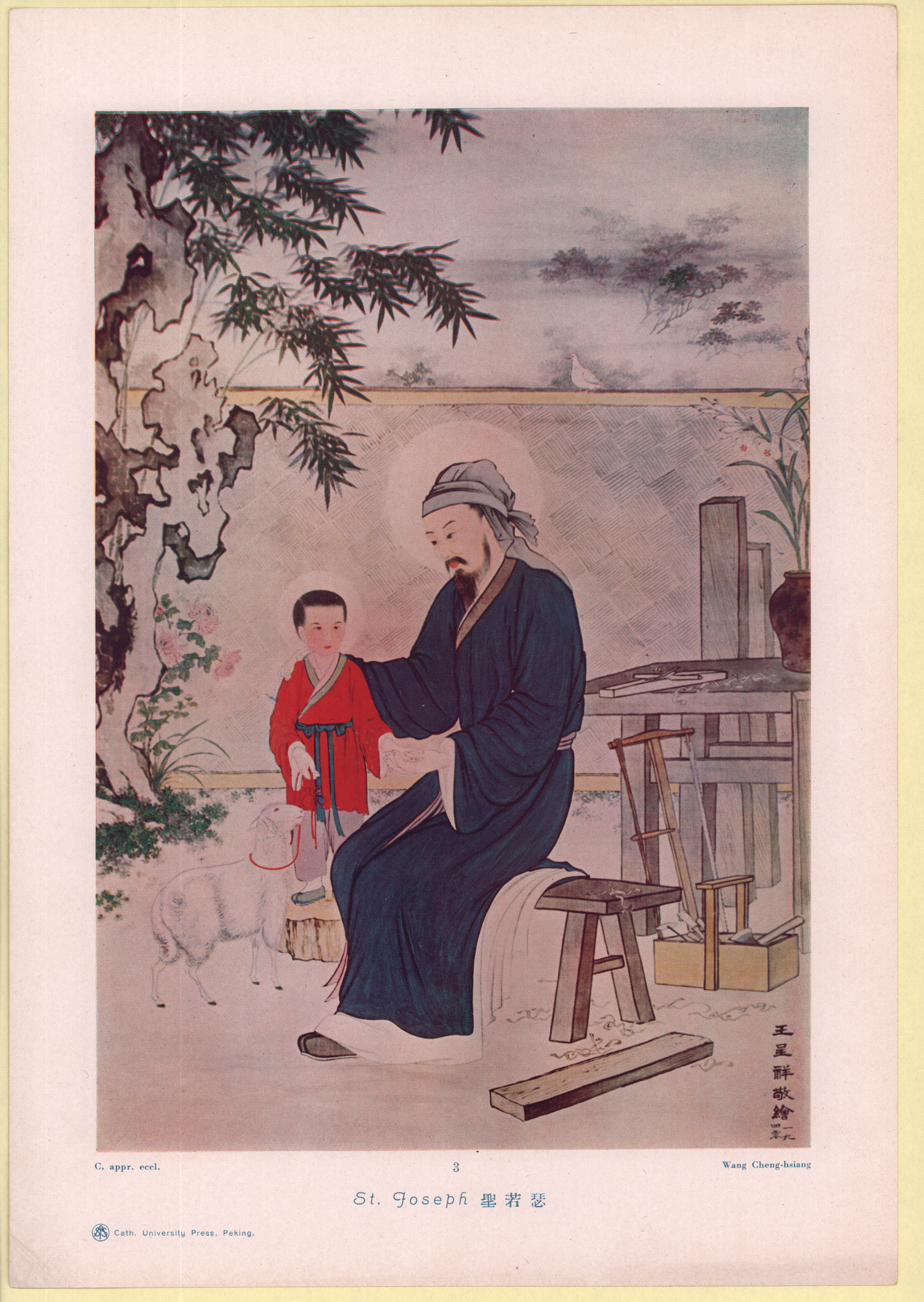

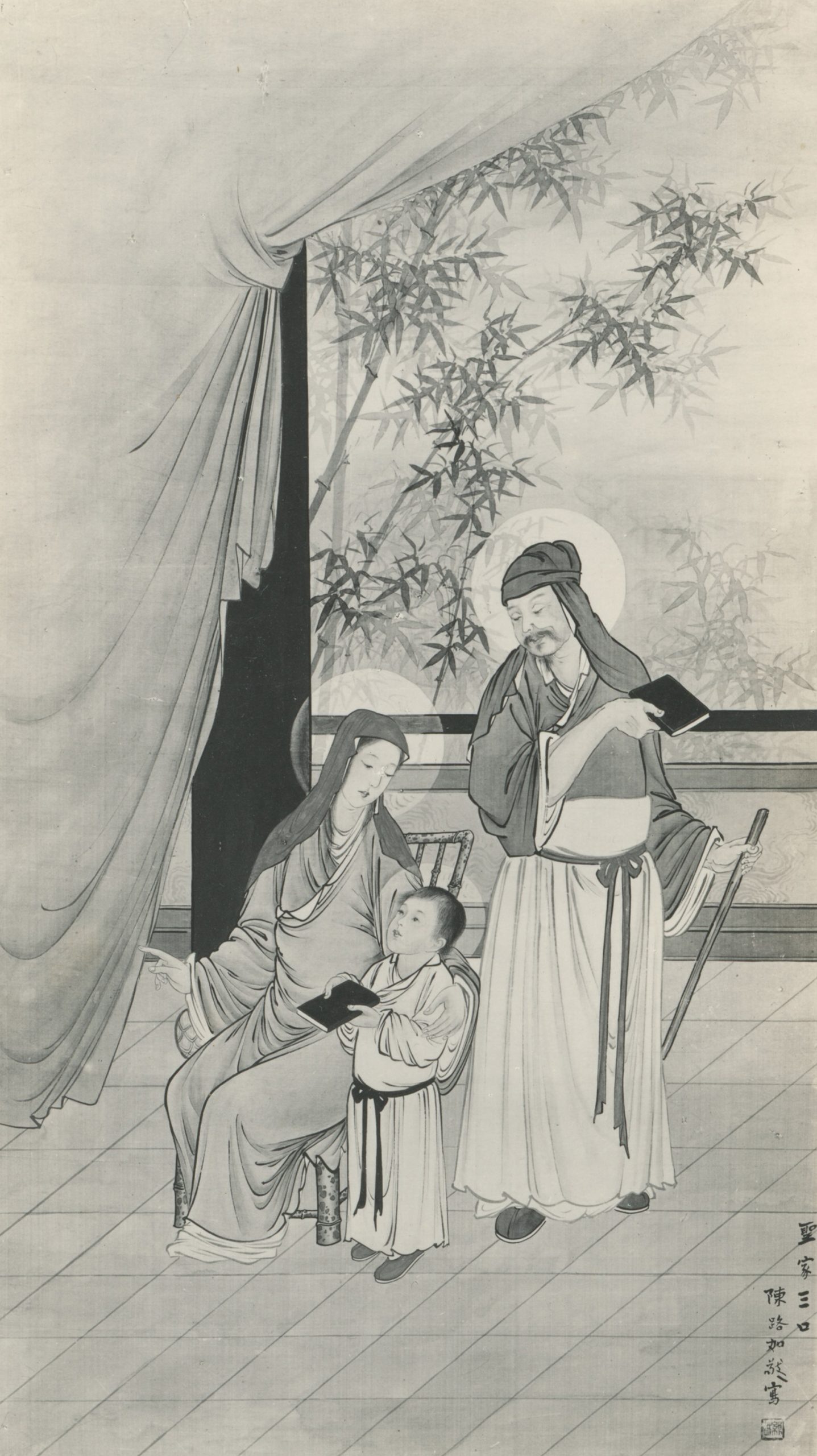

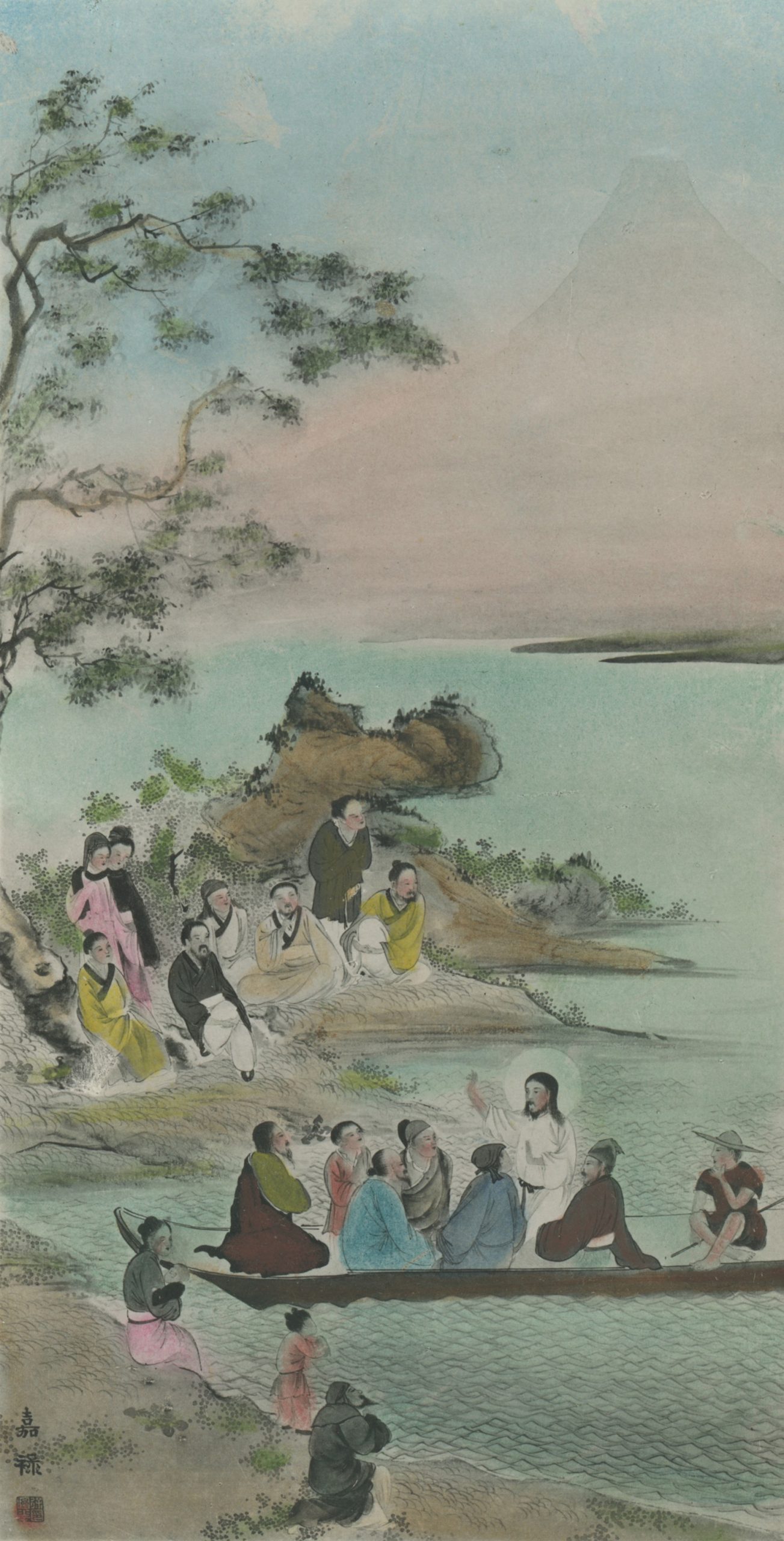

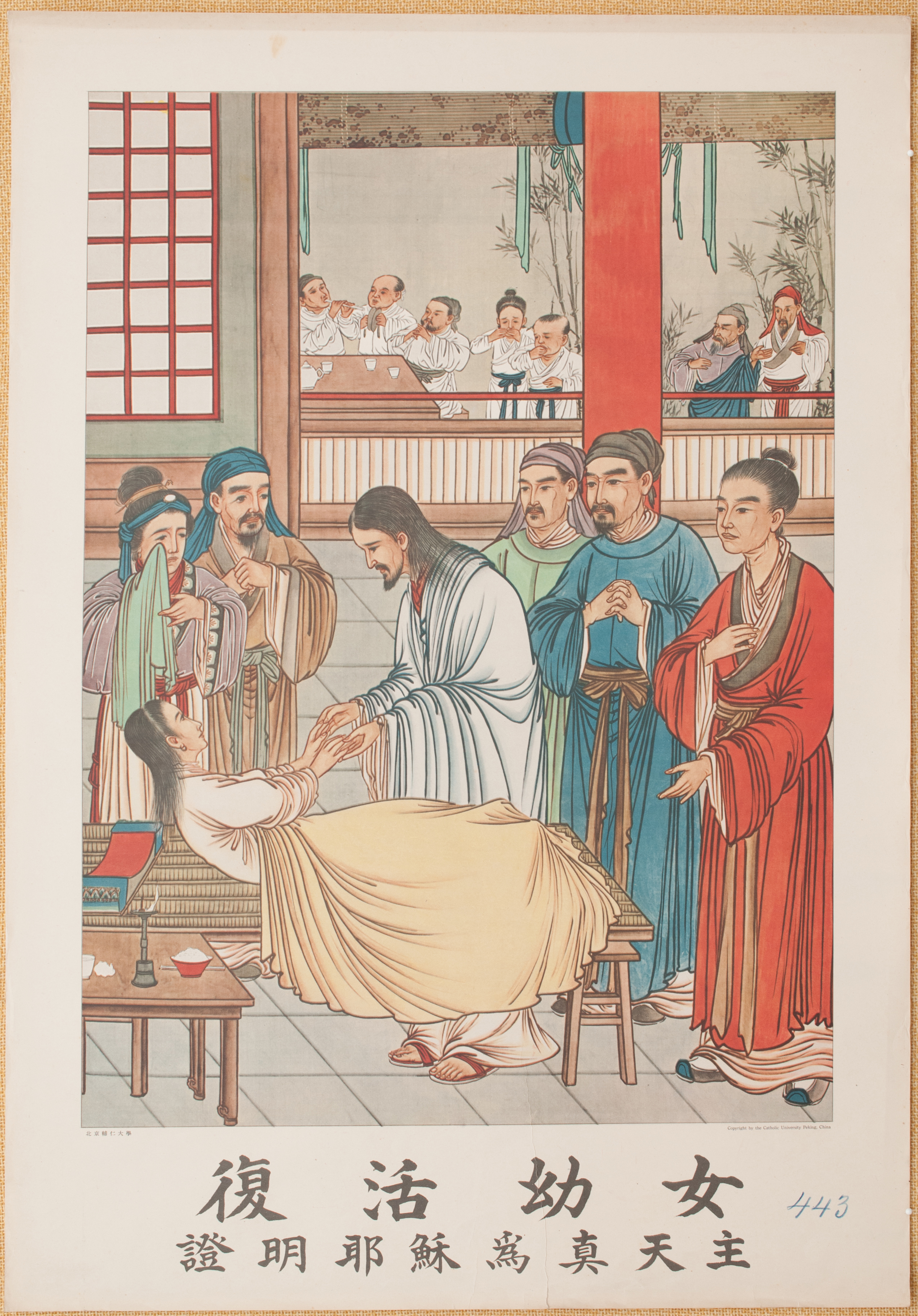

A great number of the posters and artworks collected here are distinguished by both their unique Chinese aesthetic and their creation of Chinese “versions” of Biblical events, metaphors, characters, and narratives. These versions not only depict Biblical characters as ethnically and culturally Chinese persons with traditional Chinese garb, features, and recognizable “forms” that represent familiar social actors in Chinese society such as rich man, soldiery, scholar, and so forth, but also place them in entirely Chinese settings in terms of natural and architectural environment. What caused this unique and creative appropriation in artistic expression? How did this artistic transposition of Christian narrative serve to communicate Christian meaning in its unique historical context of China at the turn of the 20th century?

“Making” of a Chinese Christ

The Christian tradition of expressing Biblical narratives and religious truths through highly expressive artwork for a largely illiterate audience is centuries old, ranging all the way back to the early days of the post-classical Roman church. Thus, for these posters – just as it was for the long tradition of religious artwork it follows – the artwork itself holds more meaning and function as the stronger locus of expressive connection between artist and audience. Even more importantly, centuries of Christianity’s encounters and inroads into China have also left behind a tradition of a faith adapting itself to local forms and attempting to integrate itself to Chinese sensibilities and worldviews. Scholars point, for example, to Matteo Ricci’s cultivation of a Confucian-scholar image in the Qing court and attempt to explain Christianity in Confucian terms.

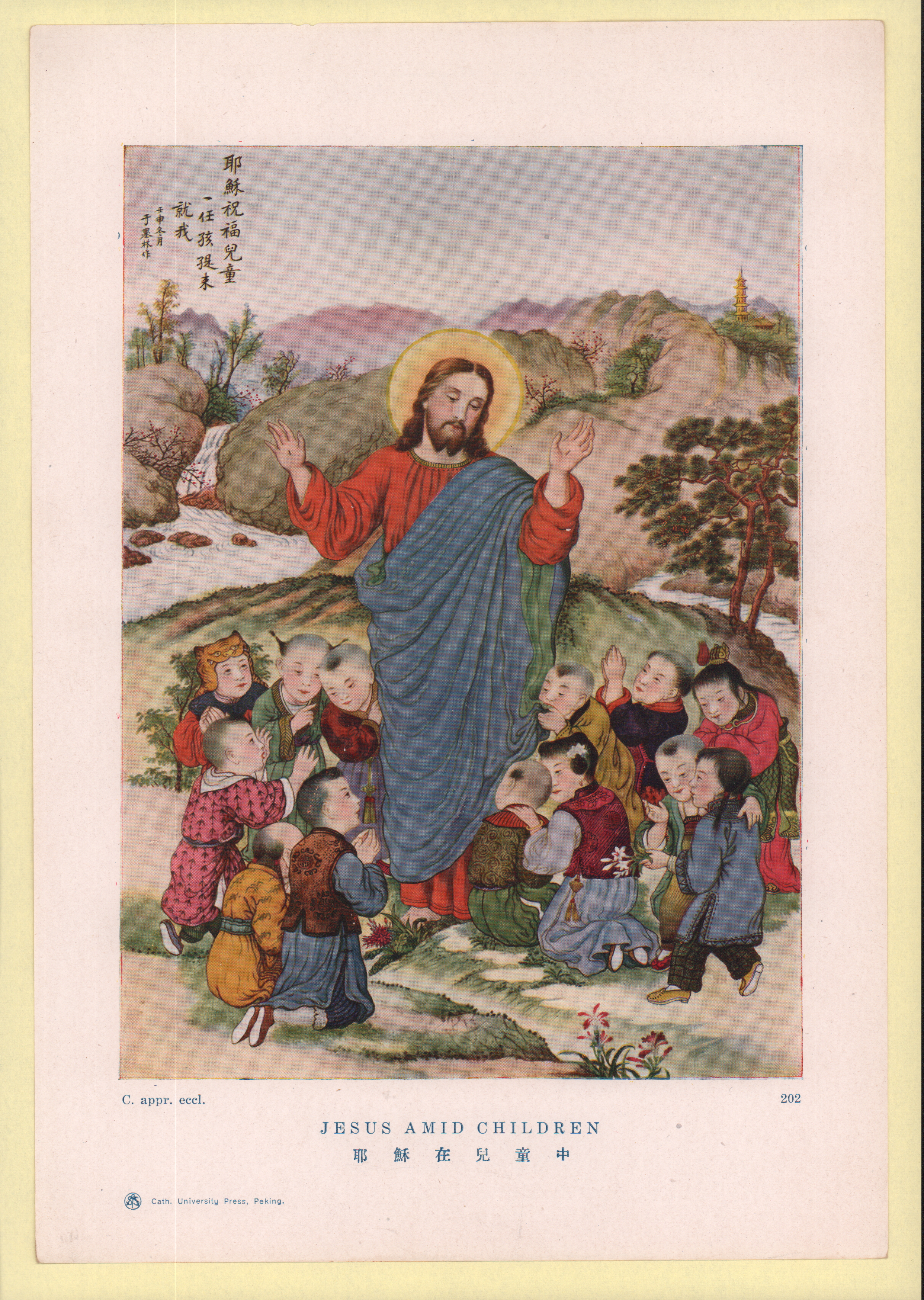

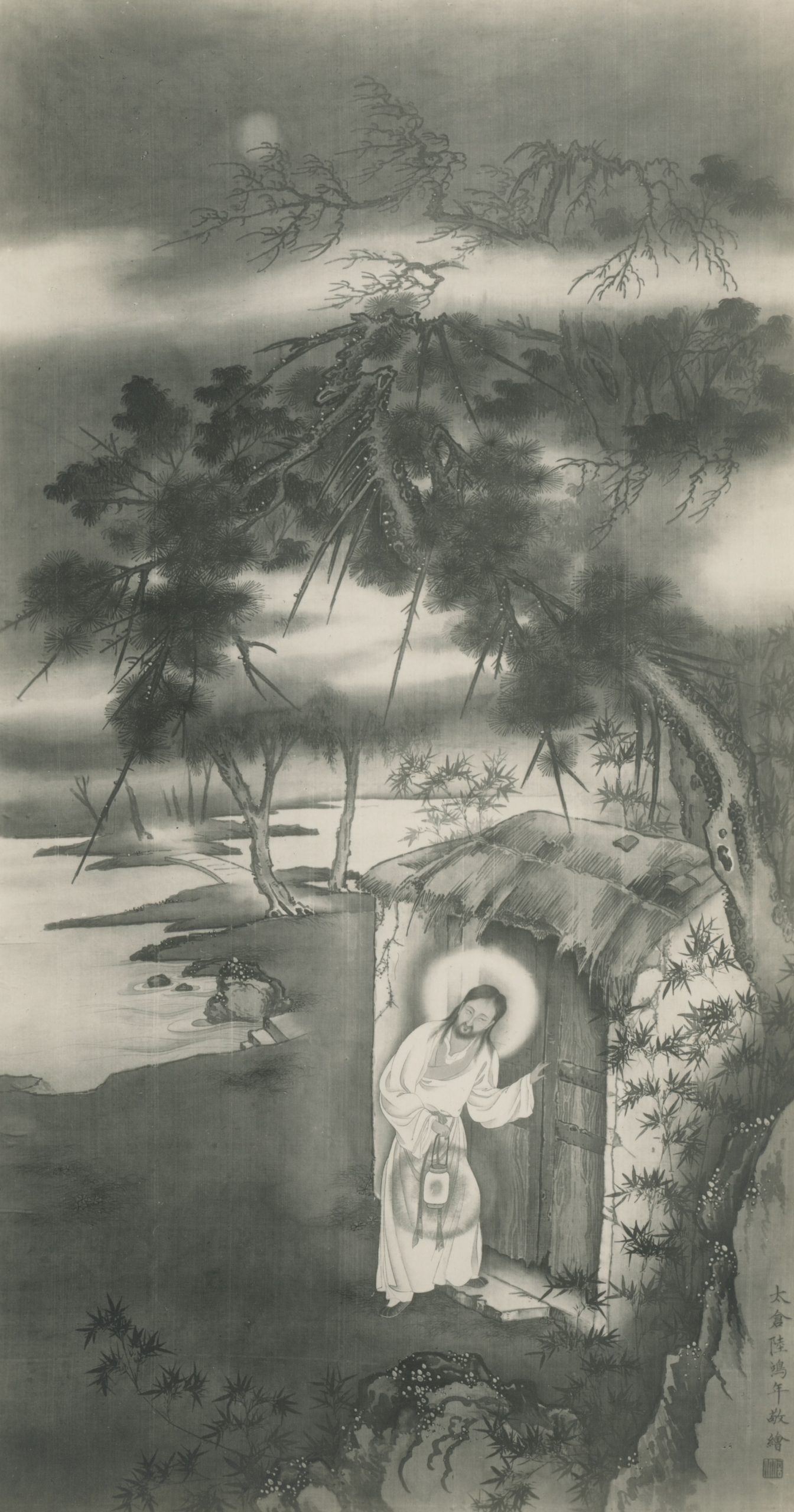

But what does the combination of these two traditions create, and more importantly, what purpose does it serve? Perhaps one could explain by saying that the Chinese Christian artists involved were simply using styles they felt most skilled in. But that, I believe, does not explain the extent of the “transposition”, and deeper rhetorical and cultural meanings have to be found. On one hand, works such as these seem to appeal to a Chinese audience by positively drawing on established frames that would convey meaning and value immediately instead of requiring interpretation. This would function on the level of the “aesthetic” values structuring the artwork: in many of these, the artwork features smaller human figures placed within a much larger environment that lays heavy emphasis on nature. There seems to be, in all of them, a minimal and often dominating presence of bamboos, willow trees, fading background mountains, and water. This reflects the traditional Chinese style of “shan shui hua” (山水画) as well as gentle, wavelike brushstrokes characteristic to Chinese ink painting.

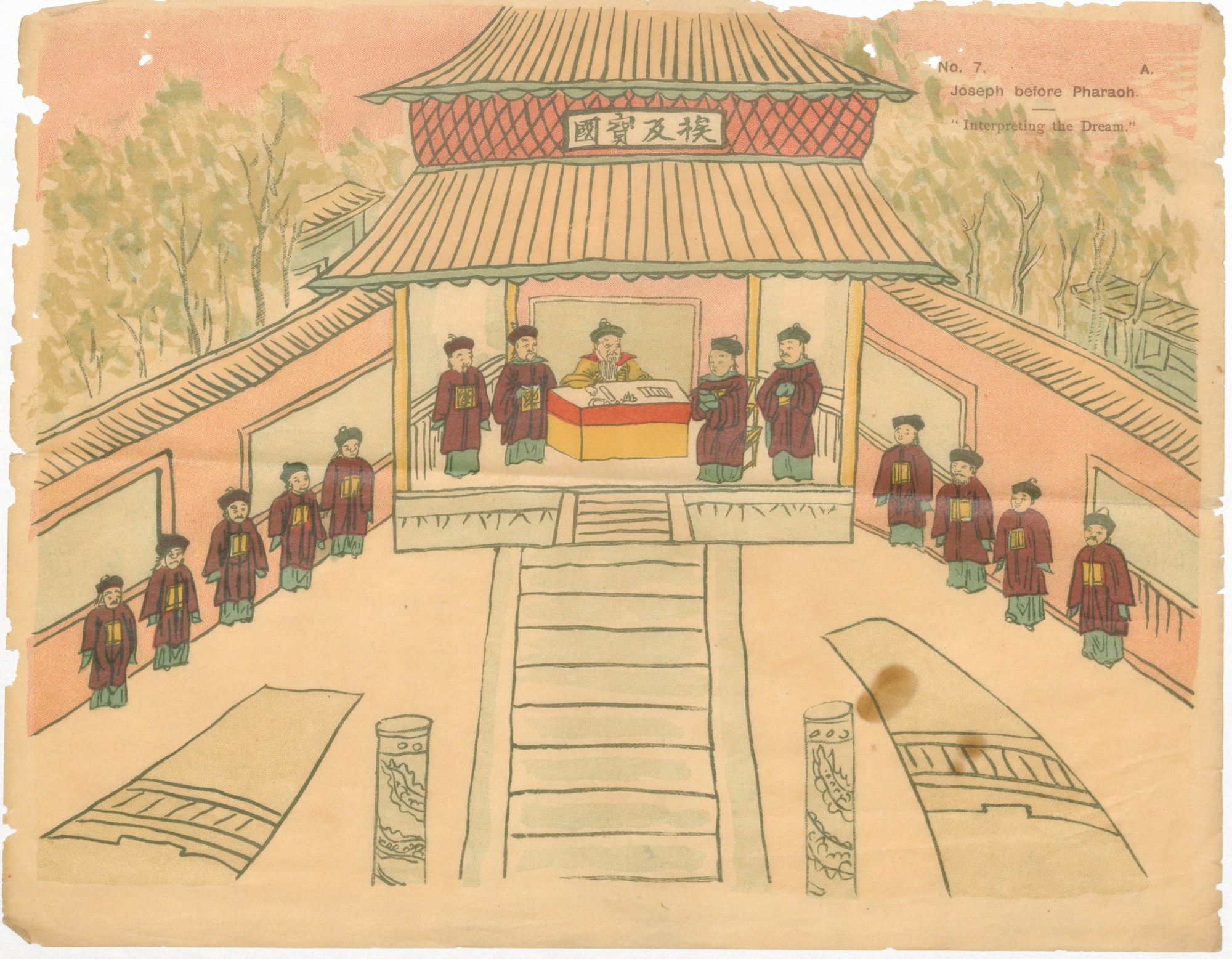

More substantially, this appeal to established experiences also works by reflecting

actual physical and social settings and “looks” present in familiar Chinese

everyday life. In this painting of the Genesis story of Joseph being judged,

for example, one sees what is basically a Chinese imperial “yamen” with a

plaque noting “Kingdom of Egypt” / “埃及宝国”.

Other examples include depictions of Biblical characters in traditional Chinese garb, or other images showing recognizable archetypal characters such as boatman, rich merchants, scholars,

or soldiers. What this appeal to existing frameworks of meaning and experience

achieves is a communication of Christian meaning and narratives in a way that

doesn’t require an absent interpretative context that would be impossible to

provide effectively. An average Chinese person would have trouble understanding, for example, a historically realist depiction of Pilate’s court during judgement of Christ. But a depiction that shows these characters and settings as their Chinese analogues would allow instant recognition and understanding. The artistic transposition in these artworks thus functions as an indispensable storytelling tool.

Against the image of “Yang-Jiao”

On the other hand, such an artistic move would certainly have been not just an attempt to positively appeal to Chinese sensibilities, but also to

“negatively” avoid associations with the foreign influence, imperialism, and colonialism that anti-Christian attitudes at the time associated Christianity with. The 1920s and 30s, when most of these artworks were composed, was marked by strong nationwide surges of nationalistic and anti-imperialistic sentiment. As one Chinese scholar writes, it is exactly this “surge of nationalism that pushed Christianity to the cusp of anti-imperialist movements.” In its contemporary context of nationalism, rejection of tradition, and the direction of xenophobia towards Christianity as “cultural imperialism”, the Christian storytelling task of these posters would have further faced significant challenges to its message as alien and imperialistic.

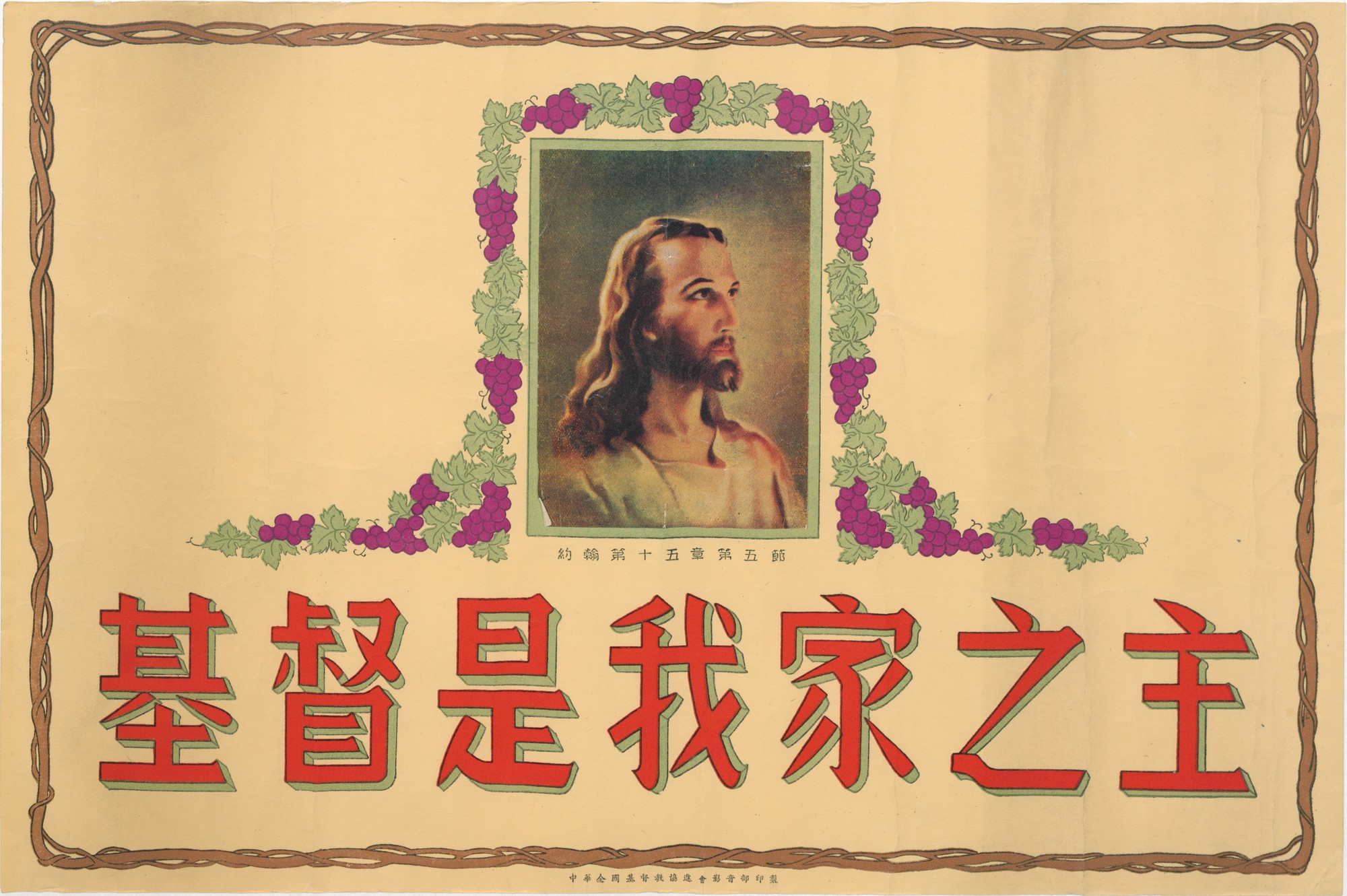

As such, the artistic transposition of Christian content into Chinese form would also have been a “negative” move to disassociate the faith from its traditional image of being a “洋教” or western religion, as a cultural product of “洋人” meant to bring them cultural influence over the Chinese people. Viewing some of these artworks through this interpretive lens, we can see the strongly negative connotations that could’ve arisen from Eurocentric depictions of a white Christ.

Such depictions would have not just had connotations of imperialism, but also simply being “alien”, where one would see stories depicting alien foreigners being healed and saved as alienating to themselves. But I think this artistic transposition should also not to be reduced as a pandering to xenophobic and anti-foreign national sentiment that somehow “betrayed” or sold out orthodoxy. With the benefit of post-colonial hindsight, we can view from our perspective that western Eurocentric depictions of Christ as a white Caucasian, paired with Eurocentric hegemony of the faith within its own philosophical and cultural frameworks, was itself a form of “localized” or particular appropriation of Christ in an image. In this sense, the faith was in fact guilty of being a “洋教” or foreign religion in that it had remade God and the dominant characters of Christian history after its own western image.

The “In-between space” of Christian universalism

What these artists accomplished was thus a kind of “universalization” of Christianity through a move to localize it. By depicting Christ and Christian narratives in seemingly historically inaccurate ethnicity, garb, character, and settings, these artists were communicating a message of universalism: Christ is not the white man’s god, but also our God, savior, healer, and teacher. His resurrection, teachings, and work of healing is one that is relevant to us as well. Christ is not in essence a white European man and his message and work directed only towards the same people colonizing us now, but he is our own and looks like us as well. That being said, I make no strong claims of arguing this from research of the inner intentions of these artists, but only from the rhetorical effects that this move must have had in its contemporary context.

In conclusion, the cultural message behind this artistic transposition was a localization and reclamation that simultaneously universalizes Christian identity and meaning. These artworks demonstrate a distinct level of cultural awareness and independence of Chinese Christian artists, who adeptly carved an in-between space of Christian art in Chinese form in challenge to contemporary trends of exclusion and alienation.

Bibliography

Levenson, Joseph R. Confucian China and its Modern Fate: The Problem of Intellectual Continuity. Berkley: University of California Press, 1958.

刘畅,“‘五四’语境中的基督教新文化运动”. 江西社会科学 B9, no.5 (2012). Accessed 3/5. http://rdbk1.ynlib.cn:6251/qw/Paper/506522#anchorList