As Christianity expanded in China, the church underwent many changes. One significant development was the role of women in the church. Like many other cultures with a strong patriarchal structure, women were often subservient in the church. However, Chinese women were also influential in the continued spread of Christianity. Many contributed to evangelistic efforts as pastors, deaconesses, and prominent community members that ministered to those in their community. These women were also known as Bible Women. In her chapter on Bible Women from Jessie Lutz’s Pioneer Chinese Christian Women: Gender, Christianity, and Social Mobility, Ling Oi Ki discusses the life of these women during the late Qing period including the challenges they faced in their ministry. Ling specifically defines Bible Women as, “Chinese Christians who, after several years of training by missionaries, were employed by the missions or supported by the Chinese church as evangelists.”[1] The posters I have selected depict the world of these women and their ministry from their depictions in the domestic and evangelical spheres as well as the struggles they faced as Bible Women.

Domestic Evangelism

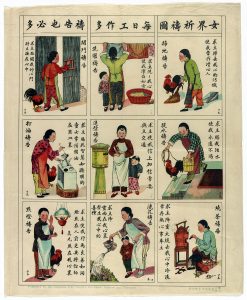

It is difficult to completely distinguish between the role of the Bible Woman in the house and her evangelism because these women often utilised their dominion over the home and domestic life in their ministry. In fact, their ties to the domestic sphere were seen as advantageous in the missionary world since China’s highly sex-segregated society meant there were some spaces that were exclusive to women and it was unthinkable for men, especially foreign missionaries, to inhabit these spaces. [2] Additionally, the missionaries were able to reach more rural communities more effectively. through these women by utilising her “lineage network.” [3] Many of the posters featured on the Chinese Christian Posters site tend to depict the woman evangelising through family. The poster on the left by Yu Liang displays congruence between the woman’s domestic life and her spiritual life, prescribing prayers for every domestic task done by the woman at home.

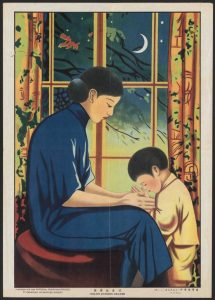

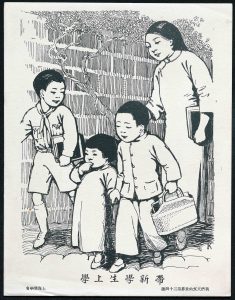

Another poster titled “Child’s Evening Prayer” shows a mother facilitating her child’s prayer life. The third poster titled “Guiding New Students to School” illustrates a female teacher guiding three young children to school just as the name implies. These latter posters speak to the role many Bible Women took up in mission work which involved spiritual and educational development. [4] Many Bible Women often made home visits to meet their students’ parents which was sometimes combined with teaching female students how to read and write. [5] Specifically in the Catholic missions, women were highly instrumental in the religious education of young children and other community members. [6] The Missions Etrangères de Paris (MEP) stationed in Northeast China was especially strict with their Christian Virgins–essentially celibate female missionaries–when it came to religious knowledge, expecting that these women had “the most advanced religious knowledge” so that they might teach it to the “Christian children and catechumens.” [7] It was not uncommon for women to also evangelise at the home, in some cases this was beneficial to reach communities that lived far away from the missionary churches. [8]

Tension Within Ministry

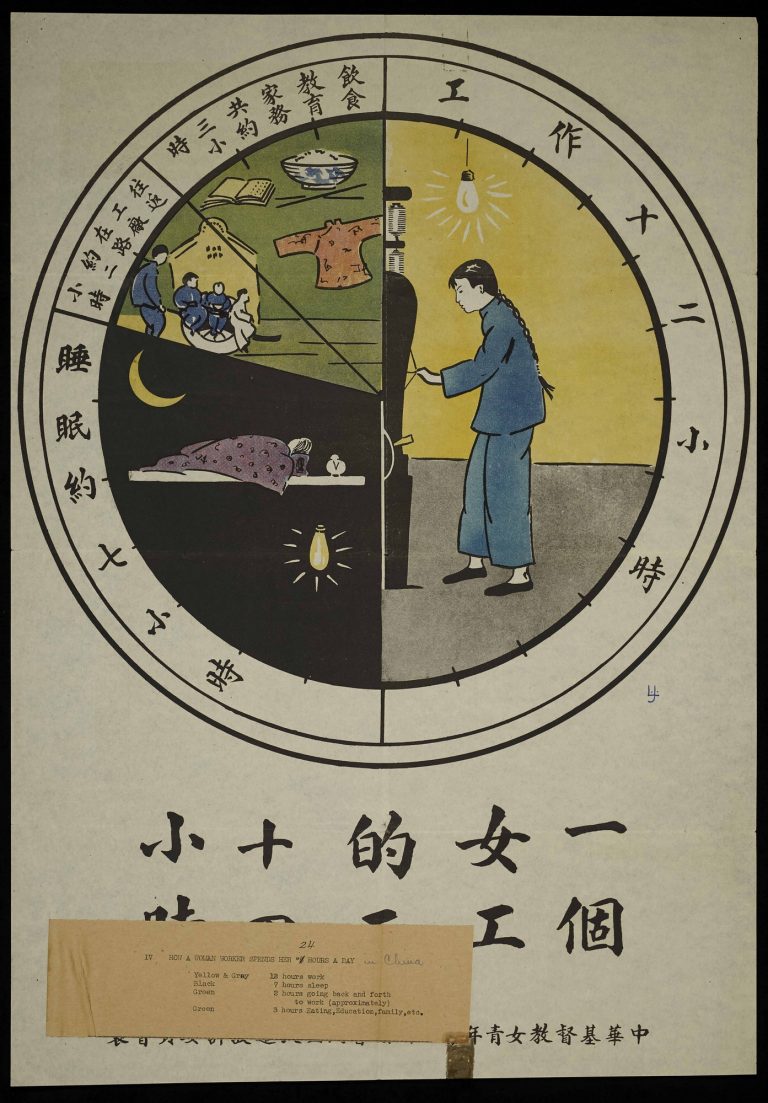

Ling also articulated in her chapter that many of these Bible Women were subjected to many challenges in their line of work as female evangelists and missionaries. One of these challenges was overworking. According to Ling, many Bible Women experienced illness and injury in their work because they had to maintain their initial duties of house labour and child rearing on top of their ministerial duties which resulted in exhaustion. [9] This work ethic is depicted in the following poster titled, “How a Woman Worker Spends Her 24 Hours a Day in China.” According to this poster, women spend half their day working, seven hours sleeping, two hours commuting, and the remaining three hours are dedicated to eating, education, and household chores.

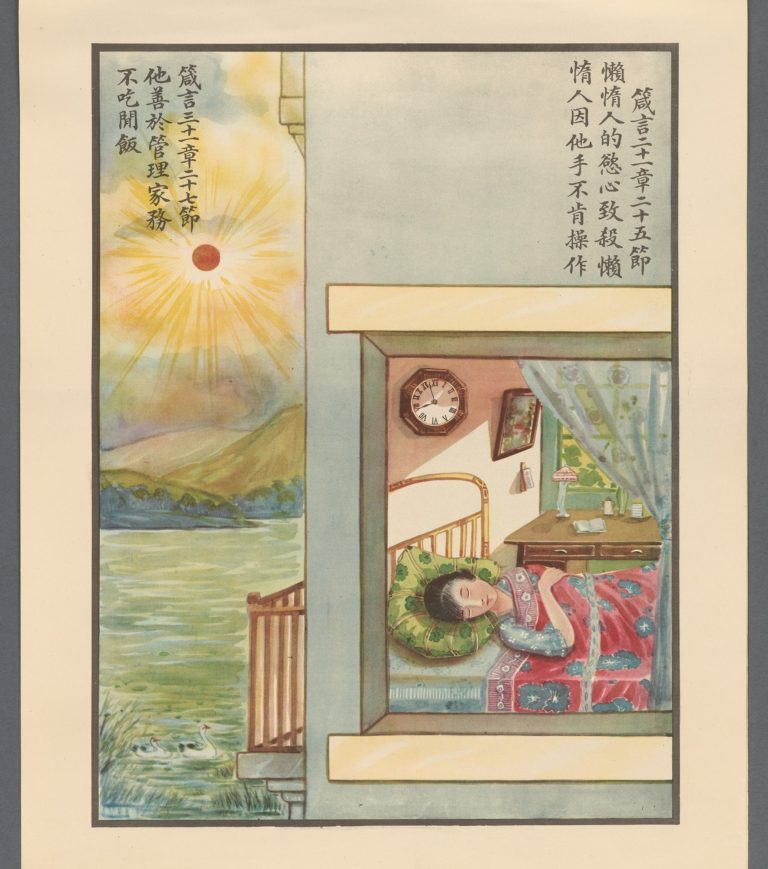

There are also posters that condemn women who do not work such as this poster titled, “Laziness.” On the poster, there are two Bible verses from the book of Proverbs and they read, “The sluggard’s craving will be the death of her, because her hands refuse to work,” and “She watches over the affairs of her household and does not eat the bread of idleness.” These two posters communicate clearly that women were highly encouraged to be active in their work–not just in ministry–but also in the upkeep of her household. In fact, the second poster implies that it is unbiblical for a woman not to be working hard everyday. The MEP held similar values for their female missionaries, except they had more practical applications for their Virgins, requiring that they pay a fee of 300 diao to join the mission as evidence that the women had jobs and were working. [10] However, this was seen more as a line of security for the Virgins since “economic dependence would make Christian Virgins very vulnerable” and it solved the financial issue the mission was undergoing by requiring a minimum admission fee since only financially capable women could be admitted into the institute. [11]

Besides overworking, Bible Women were also still subject to the established gender norms of Chinese and American society that placed them much lower than men in their field. In all of the posters shown in this exhibit, the man is not present in the maintenance of domestic life. Of course, there are other posters within the collection that do depict both the father and mother facilitating the spiritual development of the family, but rarely was there a poster depicting only a father in the house or with the children. In this poster titled "What's Your Hope," a mother and her two children are guided by the father in worship. This emphasises that while the woman is indeed in charge of directly educating the children and ensuring household practices are in line with Christian practices, the man is still traditionally in charge of guiding the larger practices of the faith. This was evident throughout missions all over the country. Tension was apparent in many American denominational missions about the role of women in ministry work. [12] Many were not allowed to be ordained as preachers and were prohibited from speaking to congregations with men present. [13] Women who were married to missionary men were often not perceived as missionaries themselves despite helping their husbands in a lot of the mission work. [14]

Afterthoughts

As I was selecting the posters for this project, I could not help but think back to my Chinese-Indonesian church back home. I saw the similarities particularly in the fact that all my Sunday school teachers were men while the adult services were almost always preached by men. Like many other churches, women could not be ordained as preachers in mine. All of these things were commonplace in Chinese-Indonesian churches. Yes, there were implied undertones of female inferiority, but at least women were still allowed to have a lot of influence in my church. Or so I thought.

My mom served in my church’s synod and I have heard countless times where her male colleagues invalidated her opinions, minimised her authority, and even lied about her to church elders. Unsurprisingly, we left that church a while ago. While my mom being a woman might not have been an explicit reason for why she was treated that way, I am almost willing to bet it played a big role in the way my conservative, Chinese church treated her. Hence, it was interesting to see that while we are almost two hundred years in the future now from when these Chinese women were thriving and struggling in their ministries, we still see these same patterns emerge in today’s Chinese churches. Women are certainly treated far more equitably in churches today, generally speaking. However, I want this exhibit to remind us that while we have come a long way since the missions of the late Qing period, we still have much to do in embracing our sisters within the greater body of Christ.

Footnotes:

[1] Oi Ki Ling, “Bible Women,” in Pioneer Chinese Christian Women: Gender, Christianity, and Social Mobility, ed. Jesse G. Lutz (Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Lehigh University Press, 2010), 246–64, https://ccposters.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Pioneer_Chinese_Christian_Women_Gender_Christianit…_-_Bib le_Women.pdf, 247.

[2] Ling, “Bible Women,” 251.

[3] Ling, “Bible Women,” 251.

[4] Ling, “Bible Women,” 252.

[5] Ling, “Bible Women,” 252.

[6] Ji Li, “Becoming Faithful: Christianity, Literacy, and Female Consciousness in Northeast China, 1830-1930” (Ann Arbour, Michigan: University of Michigan, 2009), https://ccposters.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/liji_1.pdf, 183.

[7] Li, “Becoming Faithful,” 183.

[8] Ling, “Bible Women,” 257.

[9] Ling, “Bible Women,” 250-251.

[10] Li, “Becoming Faithful,” 177.

[11] Li, “Becoming Faithful,” 177-178.

[12] Ling, “Bible Women,” 256.

[13] Ling, “Bible Women,” 255.

[14] Ling, “Bible Women,” 254.