Introduction

In the 1930s, women became a growing part of the Chinese workforce. If they did not work in production, they likely worked in the home as homemakers. This is demonstrated in the first few posters I present. With the addition of disease in public awareness campaigns, they were divided into two categories: the helper and the harmer. With the impact of the New Life Movement and the emphasis on cleanliness and flushing out disease, nurses and teachers were venerated as helping to prevent the spread of disease and prostitutes were degraded as the agents of the spread. Women were used to emphasize cleanliness or dirtiness but were more likely simply victims of disease.

Women as Workers

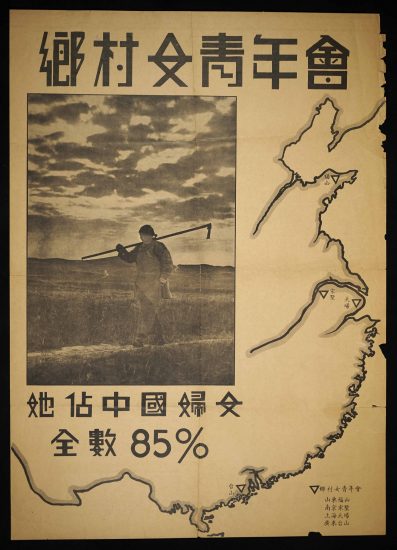

POSTER 1:

The first poster I present is titled, “The Rural Young Women’s Association,” and shows a woman farmer walking through a field with a hoe slung over her shoulder. The text of the poster says that “she makes up 85% of the total number of Chinese women.” It represents the realities for many women, as by the 1930s and 40s, “factories… replaced male workers with female workers in large numbers.”[1] This was due to the influence of protests and strikes from male workers, which forced the industries to hire women.[2] It can be assumed that the author of this poster is attempting to spread awareness about how many women were apart of the workforce at this time, which was evidently not a small number.

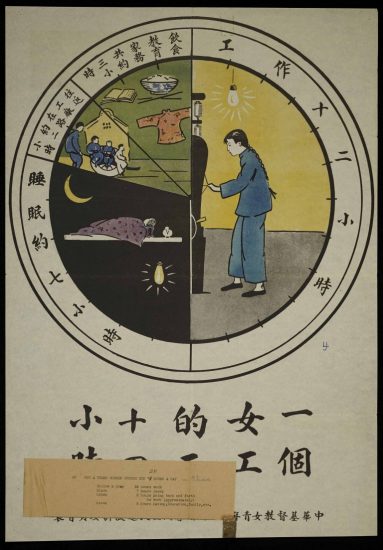

POSTER 2:

A poster from the Young Women’s Christian Organization again emphasizes this. Titled, “How a Woman Worker Spends Her 24 Hours a Day in China,” it depicts a woman inside of a clockface. The clock is divided into twenty-four parts and shows how she should spend her time: twelve hours working, seven hours sleeping, two hours travelling to work, and three hours doing household chores.

It appears from the images that the woman is a laborer and that her work involves spinning thread. There is a white spool of yarn above her head to the left of the lightbulb that illuminates her workstation. She looks focused on her job as her gaze is directed solely at her hand that pulls the thread. It is clear from the title and the images of the poster that this is the ideal for female workers.

Women In the Home

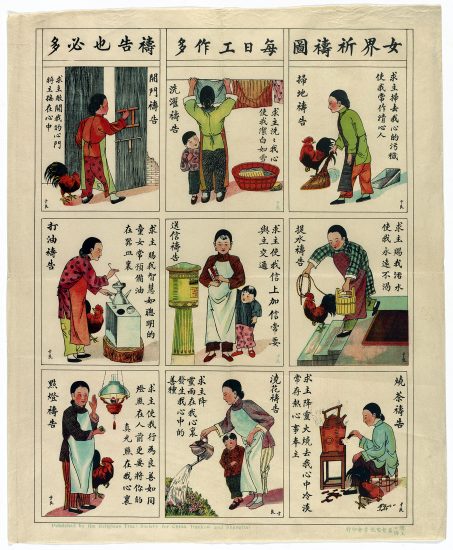

POSTER 3:

Yet, in my searches on the site, these were the only two posters I could find representing women workers. But there is another possibility for the kind of work women could do at this time: working in the home. The third poster is titled, “Women’s Prayer Pictures,” and depicts a series of nine situations of a woman doing household tasks. They range from sweeping and doing laundry to fetching water, boiling water for tea, and even watering the plants. Each situation is accompanied by a prayer.

As the poster was produced by the Religious Tract Society, it can be assumed that these prayers are meant to be said by the woman performing the tasks, perhaps even as she completes them. For example, the prayer for lighting the lamp is, “Lord, please make my action as good as light to share before man. May your true light shine in my heart.” Not only is it indicative of the woman’s place being in the home, but it shows that she does the chores for her husband and God. For Christian women, it appears that organizations such as the Religious Tract Society wished for them to be content while completing chores at home. While it may be difficult to infer that this was the woman’s only job, I would argue that completing these tasks would require more hours than the three indicated by the poster of the ideal female worker.

These two scenarios represent the majority of cases for women in China in the 1930s and 40s. With the addition of disease, there are two more representations: the helper and the spreader. The helper is shown by women being nurses and teachers, while the spreader is demonstrated by showing women as prostitutes. These pathways were not particularly common for women but were possible. As for the nurse, this profession required higher education and the funds to receive the degree. Thus, it would not have been possible for many women. But it is wrong to claim that these opportunities did not exist; by 1908, there were three missionary schools for women and the opportunity for coeducation with men in medical schools.[3]

Women and Disease: Helpers or Spreaders?

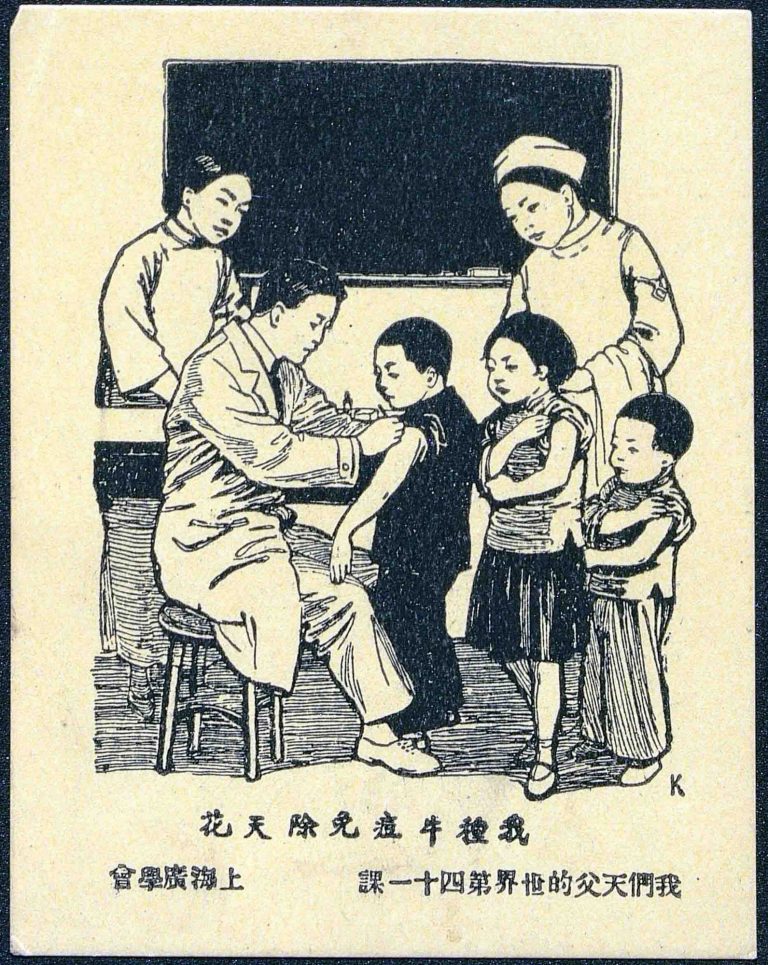

POSTER 4:

The next poster is titled, “I Get Vaccinated to Guard Against Smallpox,” and depicts a scene of a classroom where a male doctor is giving the children the smallpox vaccine. Notably, there are two adult women present in the room: a teacher and a nurse. Their presence is “the result of intensive social and cultural change in the early twentieth century” as both female nurses and schoolteachers would have been uncommon at the time.[4] The very idea of a nurse would have been brought in by missionaries and was not a profession in most nineteenth-century hospitals.[5]

As the poster was produced by The Christian Literature Society for China in Shanghai, it is perhaps more understandable why the nurse and schoolteacher are female. This situation would have been much more common for foreign missionaries than for Chinese citizens. This is the ‘good’ side of women; they are actively working to help and heal people.

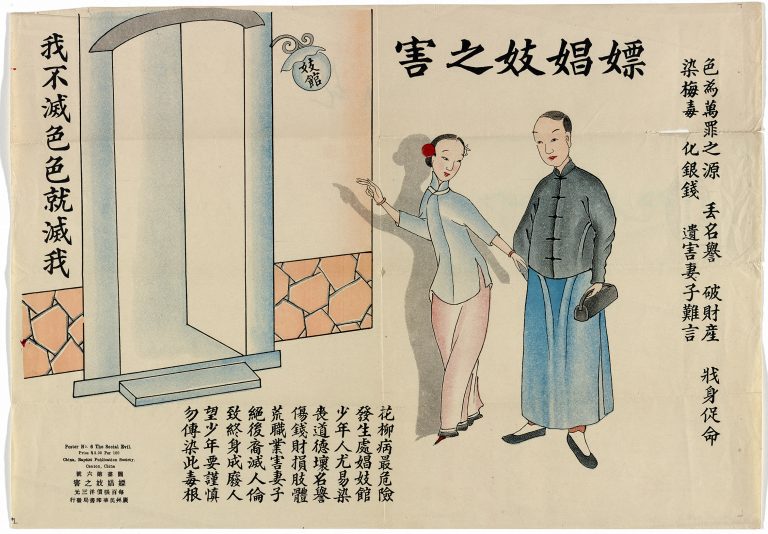

POSTER 5:

But there is another side to the coin of disease: the prostitute. See poster five titled, “The Harm of Hiring Prostitutes,” produced by the Baptist Publication Society in Canton, China. The image, a young woman leading a man into a brothel, is accompanied by warnings about lust, disease, and shame. Not only will this sin bring shame to the buyer’s wife and job, but it will cause the man to get syphilis. Here, the woman is a bringer of disease who causes the ruin of man. In the 1930s, “prostitution prospered in smaller towns that were important marketing centers or experiencing rapid growth.”[6] Prostitution was a growing problem that required a civic intervention to curb the harm it brought to society.

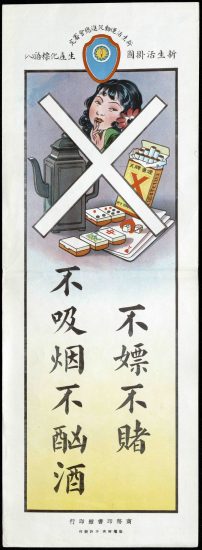

POSTER 6:

The last poster, “Do Not Go to Prostitutes or Gamble; Do Not Smoke or Drink to Excess” shows a similar sentiment to the previous poster. Yet, it comes from the New Life Movement General Promotion Council instead of a Christian publication. The New Life Movement was led by the government as a civic campaign for cultural reform. Yet, the two movements have common ground: prostitutes are spreaders of disease, which brings harm to society. It should be noted what is not present: posters depicting regular women, homemakers or workers, as recipients of disease rather than agents.

Summary

In public awareness campaigns with respect to disease, women were represented as either the nurse or teacher, the helper, or the prostitute, the spreader. In reality, they were likely more often victims of disease as workers or homemakers. The representation of women in these posters fails to consider them as ‘regular’ people and instead creates two extreme categories.

A special thank you to the Chinese Christian Posters site for their hard work finding and analyzing the aforementioned posters.

Combined Notes and Bibliography

[1] Selden, Mark. “The Making of the Chinese Working Class.” International Labor and Working-Class History 37 (1990): 54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547900009923.

[2] Ibid., 52-57.

[3] Shemo, Connie. “Women – Public Health, Hygiene, and Nurses.” In Visions of Salvation: Chinese Christian Posters in an Age of Revolution, edited by Daryl R. Ireland, 75–87. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 2023.

[4] Ibid., 76.

[5] Ibid., 76-81.

[6] Grove, Linda. “Prostitution in a Small North China Town in the 1930s.” Men, Women & Gender in Early & Imperial China, 2018, 287. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685268-00202P05.