China, more than many cultures, holds tightly to traditions of imagery and iconography, even with adopted ideas and practices. In Christianity, this practice is just as visible. In chapter 10 of Daryl R. Irelands compendium Visions of Salvation, it is noted that Chinese posters promoting Christianity and conveying its stories, visual artifacts not yet lost to time and “echoing the logic of “the Word made flesh””, show “more than mere combinations of images and texts” the simple stories and bright coloring on their surface level, but upon more deep examinations deliberate decision making on how to translate into their culture foreign ideas and parables1. Of all of the subtle decisions made, I aim to discuss the choice on whether to Adapt the core figures of biblical stories by Sinicizing them, or to Adopt them as is with little to no change.

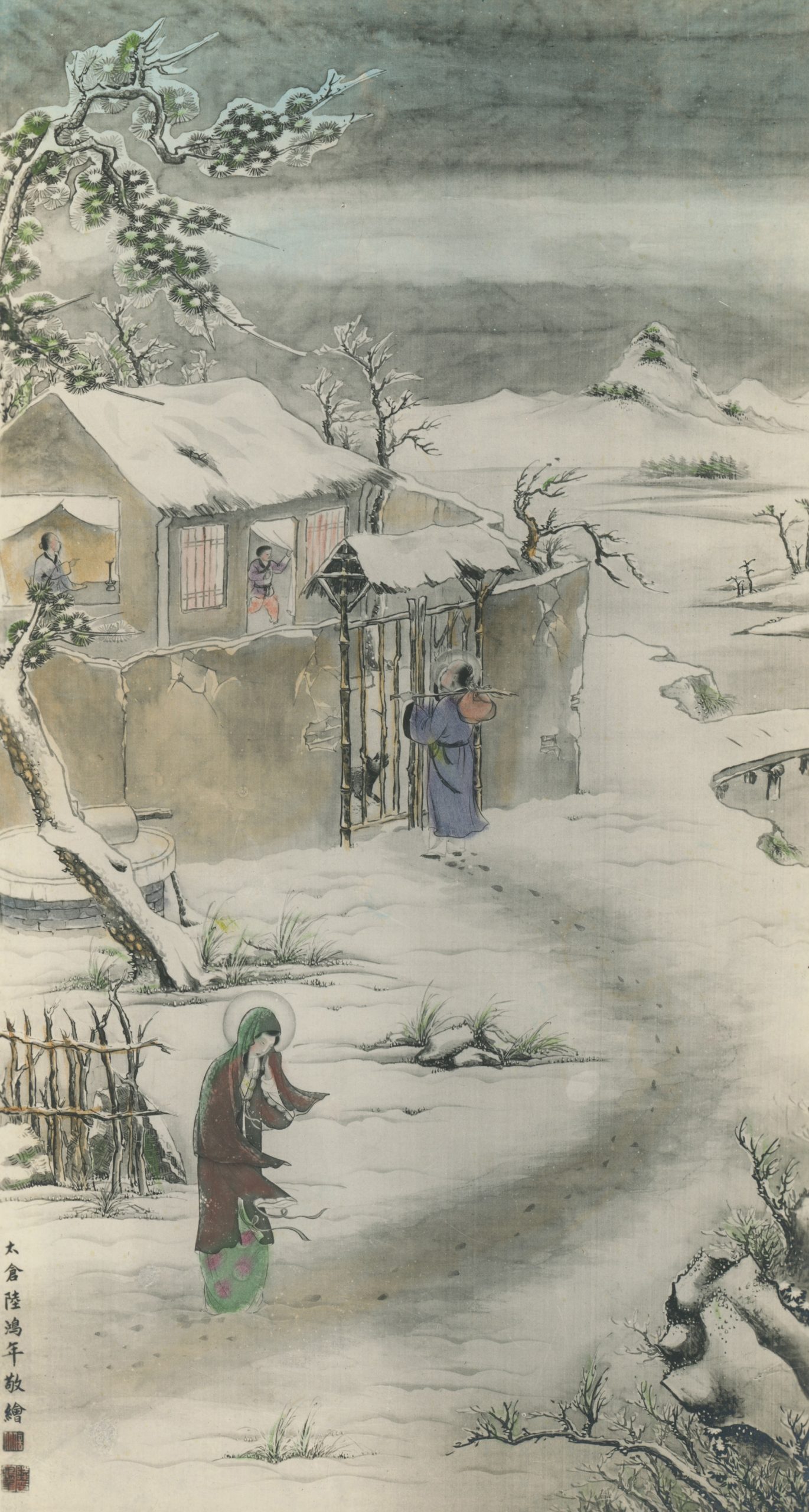

The first three posters I have chosen above all show a decision to portray the stories of the bible in a more Chinese visual space and style. In An angel announces the birth of Jesus to the shepherds by (Luke) Chen Yuandu, not only have the shepherds and angel been drawn to represent Chinese people likely to aid in self-identification for the viewers, but the more arid and warm vistas of the middle east have been completely altered to a more snowy scape. So too are No room at the inn and Birth of Jesus (by Lu Hongnian) drawn, in which Jospeh unsuccessfully seeks shelter in a snow storm at the nominal inn, and then finds it in a cave, outside of which we see the blustering snow. Though far different than the actual location of Christ’s birth, the snow matted world, closed gates, frozen river, and shear mountains in the distance all lend to the inhospitable environ, and certainly to a way largely more recognizable to most who would see the images.

However, amazingly, “While non-Chinese saw the paintings as a tremendously effective instructional tool because of the concept of self-identification” there was a “general lack of support among contemporary native clergy” who, along with many native scholars preferred “historically accurate imagery” and considered all else improper2. This strange disjoining of local preference from the perceived preference Missionaries and their far off directors’ assumed likely started in the early days of mission work, and the false belief self-perpetuated. After all, one of the first steps in preaching a foreign belief system or doctrine, as found effective by early Nestorian and Protestant monks, is the “market[ing] of their religion” requiring “knowledge of the market itself” to target the “customers” to be3. If monks, preachers, and missionaries early on found success in comparing their messages with local accepted beliefs or stories, that such a practice encouraged the beginning stages of conversion, then they would be hard pressed to risk losing said progress by pushing stories and images of alien foreigners to their flock: so thus preferring a strategy of “transplantation…and transformation.”3

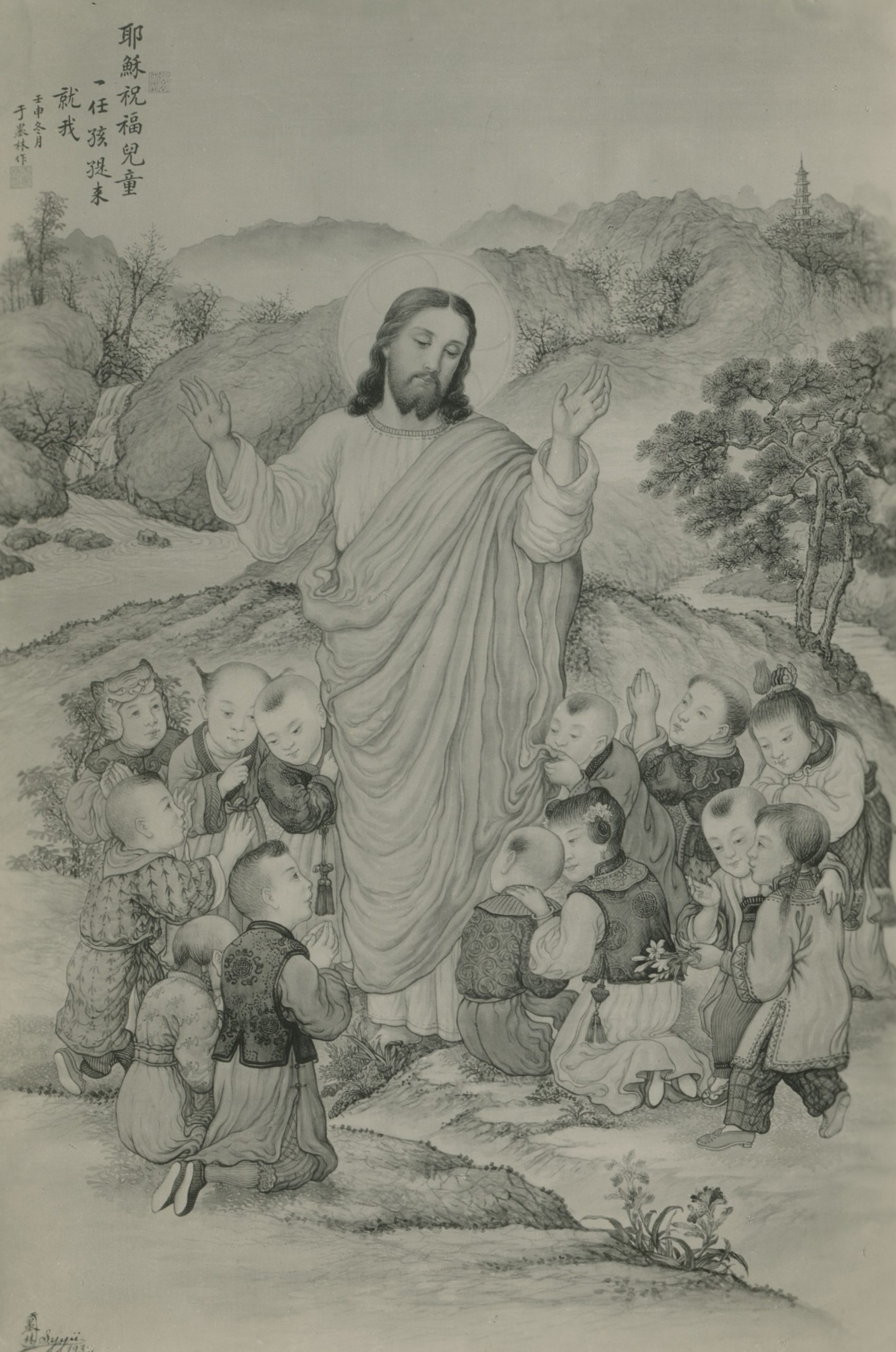

But, as above, this view was not held by the actual (albeit few) non-foreign clergy2, 3. Showing the actual preference for accuracy, posters four and six show depictions of Biblical stories with more classic depictions and imagery, and poster five is a blend. Starting with said poster, Let the Little Children Come by Yu Molin, we see Matthew 19:14 represented with a traditional portrayal of Jesus calling children to show His affection for purity and innocence. Interestingly, this poster shows Jesus in China, both demonstrating the total reach of His message, and presumably, His Grace. This style of depiction would both lend homage to the desired historical accuracy, and the present power of the Word.

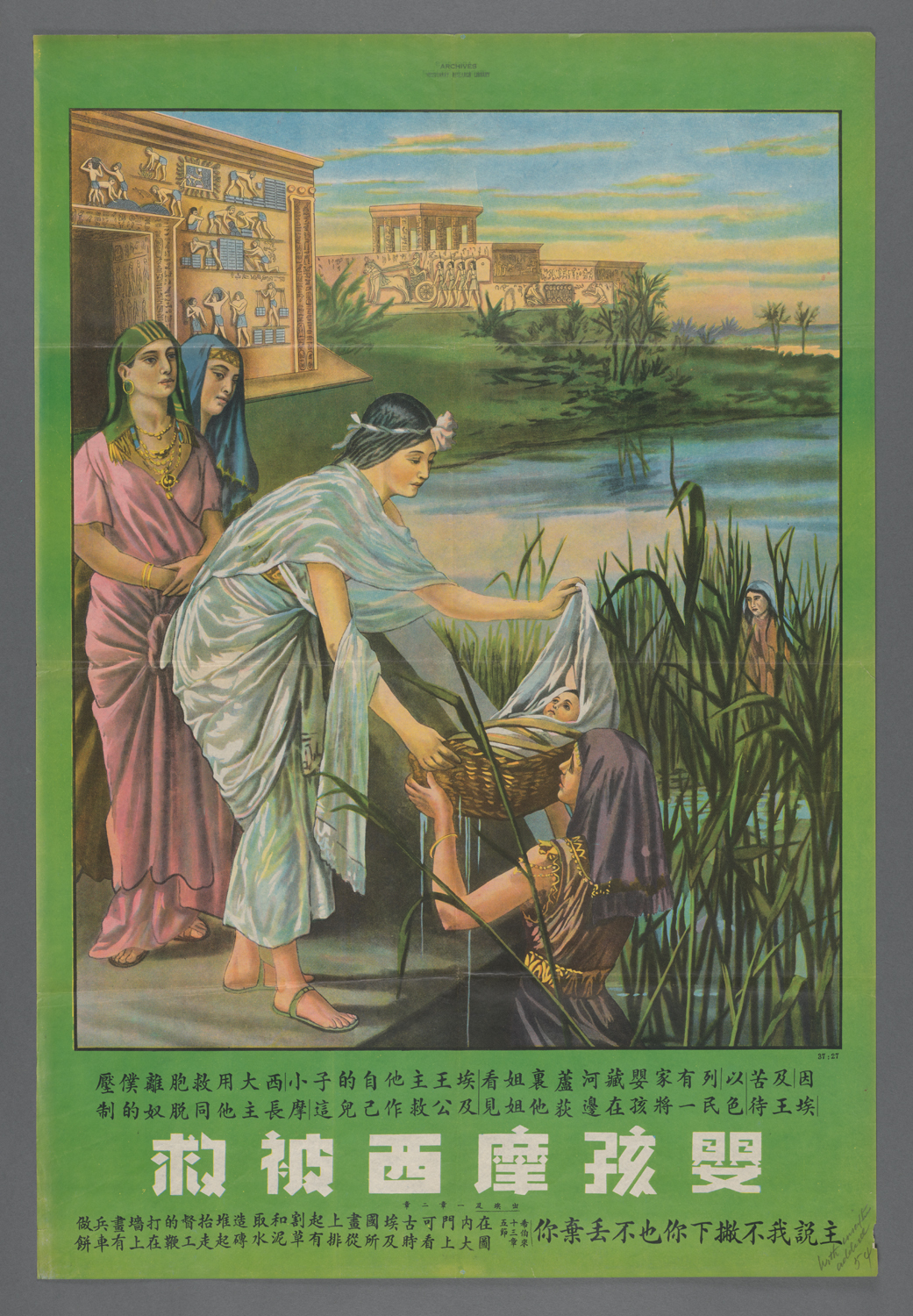

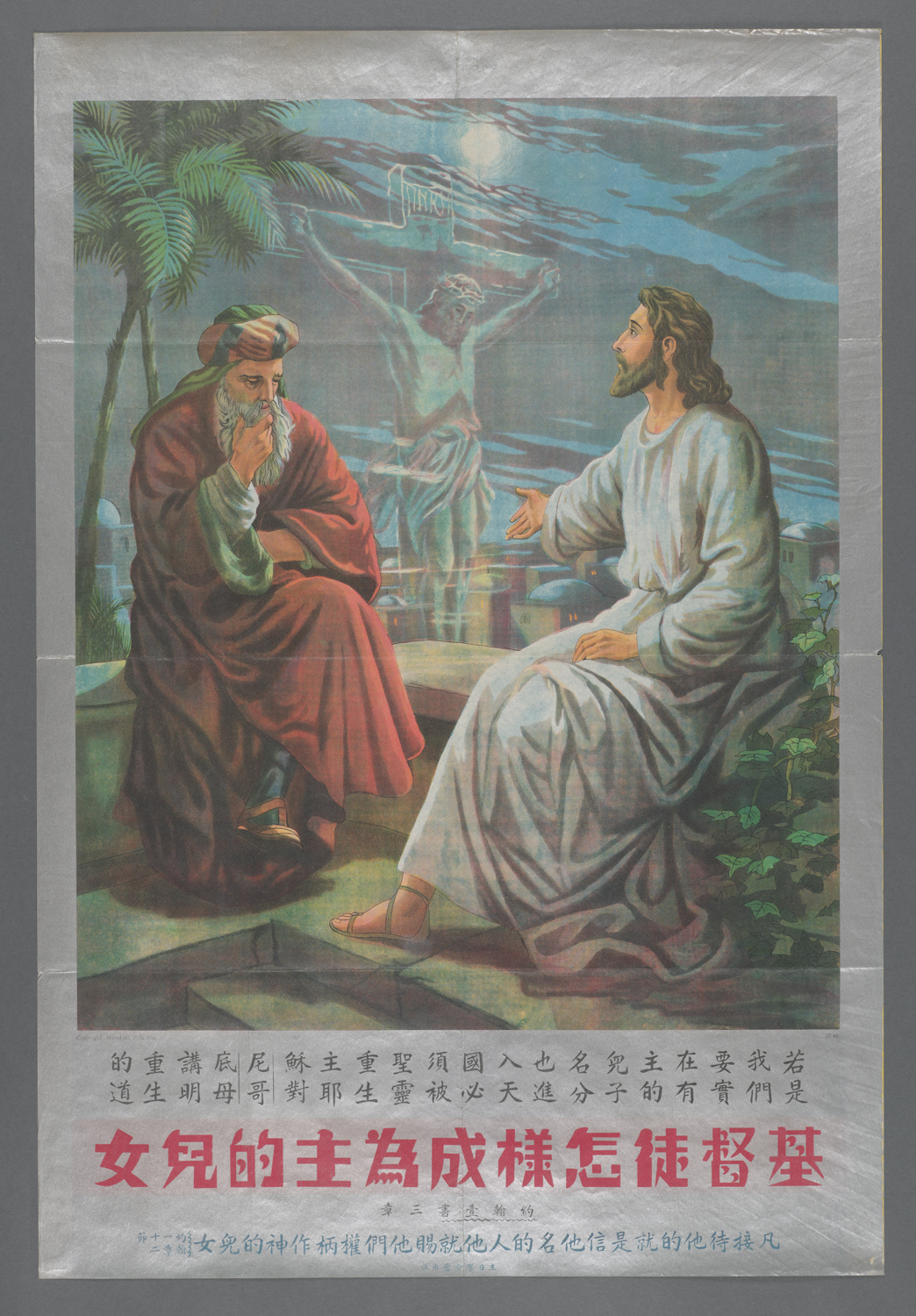

In true displays of Biblical stories set in their actual locations, Baby Moses is Rescued and How Christians Become Sons and Daughters of the Lord both show purely ‘western’ characters, or at least western by the Chinese perspective. Similarly, both accurately show the middle east as it would have been in climate, attire, and construction, including such details as ‘INRI’ on the cross, and (though exaggerated) hieroglyphs on the buildings of Egypt. These styles of posters, more representative of the wider Christian faith, have been argued to have “helped invite Chinese Christians to join in an inclusive world Christian community,” but nevertheless they remained the less common style, “…illustrating the life of Jesus grounded on a Palestinian stye [was] a rare phenomenon in Christian missions in China.”4

Perhaps in a more exceptional idea, this idea to portray a foreign core of the religion was an idea that paid off in another way. In their Lift High the Cross: The Visual Message of Popular Chinese Christianity, Ireland and Li argue that in the early 20th Century an oft-defeated China sought change and that like a new preference for foreign, distinguished clothing “…the imported cut was a way for the wearer to visibly express his commitment to be different, his belief that China had to be made new”5, change was needed elsewhere as well. Maybe in Religion as well, something not Sino-centric was for the better.

It might be best to end with the beginning of Vision of Salvation, it is emphasized that these very mass-produced posters, whether they are as I have phrased adaptive or adoptive, “were not for use in Sunday schools, to decorate a sanctuary, or hang in a private home” and carried “very clear instructions: “Please post in public places.””1 Whether trying to unite the people to appreciate themselves, to emphasize the traditions of China and her history, or to usher in new change and a respect for historical accuracy, these pieces of religious propaganda aimed to foster faith. The message was common, just the presentation differed.

1. Ireland, Daryl R., and Peter Gue Zarrow. Visions of salvation: Chinese Christian posters in an age of revolution. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2023.

2. Lawton, Mary S. “A Unique Style in China: Chinese Christian Painting in Beijing.” Monumenta Serica 43, no. 1 (January 1995): 469–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02549948.1995.11731282.

3. Zheng, Yangwen. Sinicizing Christianity. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

4. Liu, Lingshu, and Madeleine Yue Dong. “Silent Messengers: Visualizing the Growth of Christianity in China by Chinese Christian Posters, 1927-1942.” Silent Messengers: Visualizing the Growth of Christianity in China by Chinese Christian Posters, 1927-1942, 2021.

5. Ireland, Daryl R., and David Li. “Lift High the Cross: The Visual Message of Popular Chinese Christianity.” International Bulletin of Mission Research 46, no. 4 (August 18, 2022): 474–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969393221097624.

Ireland, Daryl R., and David Li. “Lift High the Cross: The Visual Message of Popular Chinese Christianity.” International Bulletin of Mission Research 46, no. 4 (August 18, 2022): 474–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969393221097624.

Ireland, Daryl R., and Peter Gue Zarrow. Visions of salvation: Chinese Christian posters in an age of revolution. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2023.

Lawton, Mary S. “A Unique Style in China: Chinese Christian Painting in Beijing.” Monumenta Serica 43, no. 1 (January 1995): 469–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02549948.1995.11731282.

Liu, Lingshu, and Madeleine Yue Dong. “Silent Messengers: Visualizing the Growth of Christianity in China by Chinese Christian Posters, 1927-1942.” Silent Messengers: Visualizing the Growth of Christianity in China by Chinese Christian Posters, 1927-1942, 2021.

Zheng, Yangwen. Sinicizing Christianity. Leiden: Brill, 2017.