Opium and the Christian Missionary Response

As with many missionary stories, there are issues of trade, nationalism, and questions of imperialism. Combined with the good and bad, this created a complicated narrative about missionaries. China in the late 19th Century is no different than other complicated missionary narratives but with one major difference: opium. The network of trade by the East India Company (particularly the opium trade) into China muddled the lines between trade and work for missionaries during this era. This paper will examine origins of the opium trade and the connection to the Christian missionaries. This paper argues that the Christian missionaries are in part at fault for the opium trade, but overtime the vast majority missionaries were anti-opium in preaching and in practice. This analysis will begin with a brief look at the history of the opium trade and the problems it created for China. It will then examine why the Christians were involved in the efforts to suppress the opium trade, and what was done to suppress the opium trade.

Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

The earliest known time of opium’s presence in China was during the 8th or 9th century being carried by Muslim traders from the West to the East.[1] However, the recreational use of opium did not really begin until the 17th century when the Dutch and British arrived in efforts to extend their opium trade network. Despite an edict banning the recreational use of the drug, the East India Company, a company of the British Empire, led the way with a monopoly on the opium trade into China. The Company indebted themselves to the Chinese due to a massive imbalance of trade coming from China (such as silks and expensive tea) and needed to establish a balance again. The cultivation and sale of opium tipped the balance in favor of the British and their East India Company.

The opium was grown and processed under the supervision of the East India Company in India and transported via the East India Company’s ships.[2] The East India Company did not sell and distribute themselves, but rather merchants from the West in China did the distribution within China itself. In some cases, Chinese officials and merchants also sold opium. The East India Company developed their market of trade in China and eventually purchased land and production means within China itself, most notably in the province of Szechuan.[3] A trade network established the East India Company’s monopoly of opium that led to and from China through these means. Eventually, the abolition of the East India Company’s monopoly allowed for other British and American competition to enter into the trade.[4] In time, the network of trade that brought large revenues and taxes became an essential piece of Chinese politics and economics in certain areas, especially places like Singapore.[5] The opium trade network’s strength bound the British and Chinese empires together. The bond was so strong that between 1898 and 1906, half of the British government revenue came from opium.[6] The British empire needed the opium trade to finance the Indian administration. To quote Jessie Lutz, “No proposal to end the East India Company production of opium in India stood a chance of passage in the British Parliament.”[7]

[1] Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, Opium Regimes: China, Britain and Japan, 1839-1952 (Berkeley, UNITED STATES: University of California Press, 2000), 6, accessed April 29, 2019, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bu/detail.action?docID=223400.

[2] Jessie Gregory Lutz, Opening China: Karl F.A. Gützlaff and Sino-Western Relations, 1827-1852, Studies in the history of Christian missions (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William BEerdmans PubCo, 2008), 77.

[3] Jon Miller and Gregory Stanczak, “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping: British Missionary Societies, the East India Company, and the India-to-China Opium Trade,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48, no. 2 (2009): 333.

[4] Lutz, Opening China, 77.

[5] Carl A. Trocki, Opium and Empire: Chinese Society in Colonial Singapore, 1800-1910, Asia, east by south (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1990), 67.

[6] David W. Scott, “Alcohol, Opium, and the Methodists in Singapore: The Inculturation of a Moral Crusade,” Mission Studies 29, no. 2 (January 1, 2012): 155.

[7] Lutz, Opening China, 78.

Opium is a highly addictive drug.[1] Though it is possible to not form an addiction, it is more common that an addiction is formed once one smokes the drug. Though it is difficult to measure how many people across China became addicted, the number was definitely in the millions..[2] Opium addiction affected all levels of society.[3] The habit was not cheap, and could ruin even the wealthiest of families to supplement an addiction. Just like today, addiction to any drug can hurt families, relationships, social status, and ruin lives. Westerners wrote of what they saw and could see “the wretchedness, poverty, disease, and death which follow the indulgence.”[4] Often times the employers of the opium networks were even addicted to the drug in a way that the entirety of their wages was spent on their addictions.[5] Aside from individuals being hurt, society also suffered. This was particularly in areas with higher addiction rates. As Edward Gulick wrote, “from a civic point of view, the smoker is vulnerable and unproductive. His demand for opium can readily serve as the basis for rackets, corruption, and smuggling…”[6] Opium created an environment of dependency, poverty, and desperation that affected beyond just the opium user. The abuse of opium became so prevalent that decrees and cries for suppression rang out all over China. This was the primary cause of the First and Second Opium Wars. Some Chinese scholars refer to the opium century as the start of the “century of humiliation” for the Chinese.[7]

[1] Brook and Wakabayashi, Opium Regimes, 1.

[2] Kathleen L. Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874-1917 (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996), 20.

[3] Ibid., 21.

[4] Miller and Stanczak, “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping,” 347.

[5] Trocki, Opium and Empire, 67.

[6] Edward Vose Gulick, Peter Parker and the opening of China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), 81, accessed May 1, 2019, http://books.google.com/books?id=N_vYAAAAMAAJ.

[7] Paul A. Cohen, China Unbound: Evolving Perspectives on the Chinese Past, Critical Asian scholarship (London ; New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), 148.

My research points me towards a threefold reason in which I will expand upon: guilt, morality, and evangelistic goals. Of course, each individual missionary may oppose opium trade for their own reason, but these three were the most common I saw during my research. First, I will expand upon this threefold reasoning and then use two different Chinese Christian posters that really embody the reasonings. In time, the effects of widespread opium abuse became apparent, and the missionaries were not blind to this. The opium trade was not just any trade but a trade that was devastating to the people of China. Because of this, the first of the three points to be discussed is the guilt felt by the Christian missionaries. Missionaries dedicated to the cause of opium suppression found their justification to act rooted in the level of guilt they felt being a Westerner and the vast supply of opium due to the trade network from the West.[1] Missionaries that were dependent on the opium trade unfortunately could not avoid participating, even if it was passively. As Lutz writes, “Opium clippers transported salaries, mail, and reports for missionaries, merchants, and foreign service personnel.”[2] Because of this connection and need to use the opium ships, guilt resided in the hearts of the missionaries once the effects of opium were seen. Many of the letters written back to the West seeking support plainly stated that the missionaries felt obligated to the cause. They felt a level of guilt involved with the trade, and they wanted to correct their wrongdoings. In many cases, the writings viewed the opium trade as a “national sin.”[3] As with any apparent sin, the missionaries wanted to fix their sin, and the only way to do this was to oppose the opium trade.

The second aspect that lead to their opposition was the reality that the opium trade hurt their main missionary goal: evangelism. One of the main hindrances is that missionaries did not allow opium addicts to join their churches.[4] This sentiment continued to be enforced by the Chinese Christians as well. Furthermore, as this case is true for many, missionaries journeyed as foreigners, and all foreigners were clumped together as one. Trader and missionary were seen as the same: a Westerner. Thus, in our case, many of the Chinese viewed the missionaries as opium distributers.[5] As distributers, they were seen as the ones that brought the pain and suffering that came along with the addiction of the drug.[6] Essentially, the Chinese viewed the missionaries as the Westerners that brought pain and suffering through the opium trade. So, how could their message of the gospel be good for a Chinese person? In many cases, the evangelical message would fall onto deaf ears.

Finally, the missionaries morally opposed the opium trade because of the nature of opium. American missionaries prominently held this belief as it paralleled a moral fight against alcoholism that took place in the United States.[7] To many missionaries, alcoholism led to destruction of an individual, and polluted the body, thus polluting the soul. Alcoholism hurt families, and it could lead to premature death as well. Similar to alcoholism, opium hurt the individuals and the families of addicts as well. In many long-term cases, the effects of the use of opium were actually worse than the use of alcohol. If someone morally opposed alcohol, it was an easy connection to oppose opium as well. The more widespread the missionaries became in China, the more they could see the consequences across cities, towns and rural settings. Missionaries shared daily contact with opium’s consequences and they could no longer be ignored.[8] As mentioned previously, opium did more than just individual consequences for the addict. Opium addiction and poverty led to rackets, corruption, and smuggling.[9] Alongside the effects of opium was the opposition to the protestant work ethic. Opium did not energize the body and was often smoked while reclining. As Lutz says, “they [the missionaries] found something inherently disturbing in the indolent pose of a reclining opium smoker.”[10] The addiction of opium held such a strong hold on China that missionaries with any sense of morality could no longer ignore its consequences.

[1] Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China, (New York, 1929), 457–8, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013161263.

[2] Lutz, Opening China, 78.

[3] Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium, 35.

[4] Ibid., 33.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Miller and Stanczak, “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping,” 347.

[7] Scott, “Alcohol, Opium, and the Methodists in Singapore,” 156.

[8] Miller and Stanczak, “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping,” 347.

[9] Gulick, Peter Parker and the opening of China, 81.

[10] Lutz, Opening China, 77.

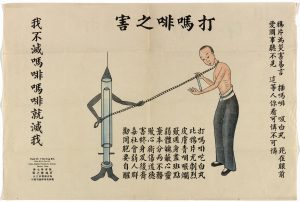

Two posters will be used because they truly embody the moral reasoning as to why the missionaries became involved with opium suppression. This first poster we see the image of a syringe holding a chain that is wrapped around the neck of a Chinese man. Symbolically, the chain being held by the syringe encapsulates the feelings the missionaries had: drugs were controlling the people. As the chain is wrapped around the neck of the man, his life is controlled by his addiction to the drugs. This is why the missionaries morally opposed the drugs. Some of the text on the poster reads, “It is easy to say that opium is a disaster. Injecting morphine and inhaling white ball, death is imminent”. At the bottom of the poster, “If I don’t destroy morphine, morphine will destroy me.” These two lines in particular feed directly into the narrative of why missionaries oppose opium and drugs: the addiction destroys the body which reflects the image of God, and that opium hurts the evangelistic message of the missionaries.

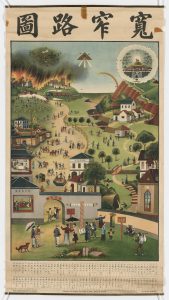

This poster displays two paths: one that leads to eternal life, and the other leads to eternal death. The path to the left is the path towards eternal death. It is lined with the social ills prominent in China in the eyes of the missionaries: drunkenness, Da Wang temple, a brothel, gambling, and fortune telling. However, it is important to note for our study that the opium den is the first stop along the path. The poster and the research show that the opium den is seen as an immoral path that leads to destruction and death. The significant thing to notice in this poster is how it embodies much of what is being discussed in this exhibit. The theology of the poster displays the desire for the Chinese person to not only live a better life without opium but in hopes that they turn to Jesus for their salvation as well.

Missionaries in China held a wide range of responses and different Christian perspectives to opium and what should be done.[1] Within those perspectives, change took place over time, and as Jon Miller stated, “we will see in what follows that the earliest British missionaries began with silence, occasionally veered into connivance, and ended with challenge—in time traversing the entire range of possible responses.”[2] However, despite the silence at the beginning, nearly every missionary in China opposed the use and trade of opium. Missionaries did not just blame Westerners for the devastation of opium. Therefore, efforts of the missionaries took place within China but also efforts were made in England as well.

In China, efforts attended directly with opium smokers as well as officials. For the churches, they did not allow for opium smokers to join. However, the churches still wanted converts so they directly worked with opium addicts to break their addictions.[3] The goal of total abstinence was expected by the missionaries, and they led by example while simultaneously working with addicts. Some treatments were given by missionaries to aid in this addiction process.[4] Many missionaries led campaigns to provide awareness against the dangers of opium through printed means such as the posters examined in this paper as well as local newspapers like The Chinese Repository.[5] Missionaries also created an Anti-Opium League that organized efforts of missionaries and locals to aid in the opposition of opium in China. These organizations could even team up with non-Christian Chinese organizations as well.[6] The efforts of these organizations gained more notoriety and were able to speak directly to the Chinese officials that took bribes to ignore the opium trade in China. Some of the efforts in China led directly to their efforts in England. For instance, missionaries gathered evidence such as photographs, journals, articles, or posters to share with anti-opium organizations in England.[7] The missionaries needed to bring China to England in order to understand the effects of the opium trade.

With the information gathered by missionaries in China, the missionaries took this back to their countries of origin and into the churches in hopes that they could inform the general public. Missionaries came and went from the West and the East frequently and thus the flow of information was constant. Missionaries shared their first-hand experiences with the perils of opium to anyone that would listen. Missionaries spoke in public meetings and church conferences attended by church members and high ranking church leaders. The hope lay with the public that their outrage would change the opinions of the British politicians, and change the laws around the opium trade.[8] Beyond work with the general public, missionaries also made demands directly to the government officials. Petitions to the central governments of the United States and the British Parliament applied pressure on lawmakers to rethink their support of the opium trade and its consequences.[9]

From silence to full-hearted effort, the missionaries made their mark on the opium trade in China. Missionaries fully embraced anti opium resistance in the best ways they knew how and their efforts were known. Unfortunately, much of their efforts fell short. The efforts against alcoholism in the United States was not equivalent to the efforts against opium. Eventually, in 1907, the Chinese and British came to an agreement to suppress the opium trade. Certainly, the efforts of the missionaries deserve some credit in this agreement. However, at this point, the Chinese government deserves a lot of the credit.[10] Though this agreement did not completely end the importation of opium, and the British still benefited, the suppression significantly lessened the cultivation of opium in China. In 1911, a revolution intervened on the issue and nearly eradicated the use of opium but like most social ills, it is nearly impossible to completely erase.[11]

[1] John R. Haddad, America’s First Adventure in China: Trade, Treaties, Opium, and Salvation. (Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press, 2013), 120.

[2] Miller and Stanczak, “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping,” 334.

[3] Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium, 33.

[4] Scott, “Alcohol, Opium, and the Methodists in Singapore,” 158.

[5] Lutz, Opening China, 77.

[6] Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium, 67.

[7] Ibid., 32.

[8] Ibid., 28–29.

[9] Scott, “Alcohol, Opium, and the Methodists in Singapore,” 158.

[10] Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium, 162.

[11] Ibid., 184.

The trade of opium brought great riches to many Westerners including the entirety of the British Empire but wreaked havoc amongst local Chinese persons. Addiction spread across China from the poor to the rich with devastating results. In the midst of politics and trade lay the Christian missionaries. In some instances, the missionaries were active recipients of the benefits of the trade, while others passively benefitted. Eventually, the missionaries could no longer idly sit by because they could see the effects of opium. The effects brought guilt to the hearts of the missionaries and opposed their moral beliefs. Ultimately, opium also hurt their evangelist mission. The response to the opium trade by missionaries went from silent to activists. It is difficult to say how much of the missionaries’ efforts contributed to the eventual suppression of the opium trade. However, it is apparent that the missionaries knew the role they played in the opium trade’s devastation, and cared enough to work hard to reverse their mistakes.

Brook, Timothy, and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi. Opium Regimes: China, Britain and Japan, 1839-1952. Berkeley, UNITED STATES: University of California Press, 2000. Accessed April 29, 2019. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bu/detail.action?docID=223400.

Cohen, Paul A. China Unbound: Evolving Perspectives on the Chinese Past. Critical Asian scholarship. London ; New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

Gulick, Edward Vose. Peter Parker and the opening of China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973. Accessed May 1, 2019. http://books.google.com/books?id=N_vYAAAAMAAJ.

Haddad, John R. America’s First Adventure in China: Trade, Treaties, Opium, and Salvation. Philadelphia PA: Temple University Press, 2013.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. A History of Christian Missions in China,. New York, 1929. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015013161263.

Lodwick, Kathleen L. Crusaders against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874-1917. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996.

Lutz, Jessie Gregory. Opening China: Karl F.A. Gützlaff and Sino-Western Relations, 1827-1852. Studies in the history of Christian missions. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William BEerdmans PubCo, 2008.

Miller, Jon, and Gregory Stanczak. “Redeeming, Ruling, and Reaping: British Missionary Societies, the East India Company, and the India-to-China Opium Trade.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48, no. 2 (2009): 332–352.

Scott, David W. “Alcohol, Opium, and the Methodists in Singapore: The Inculturation of a Moral Crusade.” Mission Studies 29, no. 2 (January 1, 2012): 147–162.

Trocki, Carl A. Opium and Empire: Chinese Society in Colonial Singapore, 1800-1910. Asia, east by south. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1990.